Introduction

Organophosphates (OPs) are used to eliminate insects in farming, in some processes of industrial implementation, and in chemical warfare as nerve agents [1, 2]. The effectiveness of OP insecticides is indisputable, but their poisoning in humans and other non-target species is a growing public health issue [3-5]. OPs are poisonous to the nervous systems of the target species [6], specifically by inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity at the binding site [3, 7], leading to neuromuscular disorders via the accumulation of acetylcholine in the body [8]. People usually get exposed to OP via ingesting contaminated food, inhalation, from hand-to-mouth touch, and dermal contact with wares and surfaces having OP insecticides [7-11].

Dichlorvos (DDVP), an organophosphate pesticide compound, is implicated to be neurotoxic in mammals as they irreversibly inhibits AChE activity [7, 12]. They exhibit multitarget toxicity in different systems in the body, including the reproductive system, pancreas, kidney, spleen, brain, and immune system [13]. Apart from the clinical manifestation mentioned above from the toxicity of DDVP, the induced oxidative stress contributes to tissue damage [14, 15]

Over the years, atropine and pralidoxime have been the most effective treatments for OP poisoning [16]. Nevertheless, the effects of these drugs on cardiac oxidative stress and antioxidative parameters are unknown [17]. Atropine is the drug of choice for OP poisoning due to its ability to selectively block the effect of excess acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors in the brain and peripheral tissues following AChE inhibition by OPs. Reports on anti-oxidative efficacy of atropine in OP induced toxicity are few [14].

Citric acid is a weak organic acid found abundantly in citrus fruits, such as oranges, lime, lemon, and tangerine [14]. Citric acid is a substance known to occur naturally and has been considered a potential therapeutic agent [18]. It is a component of the Krebs cycle and found in all animal tissues as an intermediary substance in oxidative metabolism [19]. Studies indicated that citrate decreases lipid peroxidation and downregulates inflammation by reducing polymorphonuclear cell degranulation and attenuating the release of myeloperoxidase, elastase, interleukin (IL)-1b, and platelet factor [20, 21]. Citric acid is thus proven to be of value in decreasing oxidative stress [19].

Oxidative stress and inflammation are implicated to be central to the clinical complications of DDVP poisoning [15-22], and the available antidotes are not reported with potential antioxidative and anti-inflammatory capacities [22]. It became apparent that supplementing the available treatment strategies with natural antioxidants may help improve treatment outcomes by preventing the neurological sequelae of insecticide poisoning. The study found that modulation of oxidative stress and inflammation is essential for achieving optimal recovery following organophosphate poisoning, and citric acid supplementation improved the neurological phenotypes of the exposed rats.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

The University of Ilorin Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences approved the experimental protocol (reference number UIL/FBMS/AN2113).

Chemicals and drugs

Agrochemical purposed DDVP solution manufactured by Forward (BEIHAI) HEPU Pesticide CO., LTD. and distributed by Saro AgroSciences LTD was purchased at a local agrochemical store in Ilorin. Pharmaceutical-grade atropine and citric acid were purchased from a central research laboratory in Ilorin, Kwara state.

Animal care

The animals were kept in wire-gauzed cages located in the Animal holding of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ilorin, for twenty-eight (28) days. They were fed properly under a natural light and dark rhythm at room temperature with proper ventilation for a period of seven (7) days to acclimate to the new environment.

Animal grouping and administration protocols

The animals were grouped into eight (8) groups with eight (8) animals in each cage. Drugs were administered orally using an oral cannula. The procedure was performed for 20 consecutive days. The first ten days were used to establish the toxicity with repeated oral DDVP ingestion, while the following ten days were used for treatment and exposure to normal saline, atropine, and citric acid. Groups 1, 2, and 3 received normal saline (0.1 mL/kg), dichlorvos (DDVP) (4 mg/kg), then normal saline, and normal saline then DDVP, respectively. The intervention groups (4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) received control dosages of DDVP and normal saline in the first 10 days, followed by atropine (10 mg/kg) and citric acid (50 mg/kg), separately or combined.

Behavioral evaluations

On the 19th and 20th day of the treatment, the rats were subjected to behavioral evaluations for various behavioral phenotypes.

Y maze

It is well known that spontaneous alternation is a measure of spatial working memory. The Y-maze can be used to measure short-term memory (STM), general locomotor activity, and stereotypic behavior. Therefore, spontaneous alternation was assessed using a Y-maze composed of three equally spaced arms (120°, 41 cm long and 15 cm high). The floor of each arm is made of Perspex and is 5cm wide. Each rat was placed in one of the arm compartments and was allowed to move freely until its tail completely entered another arm. The sequence of arm entries is manually recorded, the arms being labelled A, B, or C. An alternation is defined as entry into all three arms consecutively. For instance, if the animal makes the following arm entries, the number of maximum spontaneous alternations is then the total number of arms entered minus two, and the percentage alternation is calculated as ([actual alternations /total alternations] x 100) [23]. Y-maze testing was performed for 3 minutes for each animal. The apparatus was cleaned with 5% alcohol and dried between sessions.

Elevated plus maze (EPM)

The rats were exposed to two trials in the elevated plus maze (EPM) paradigm to evaluate amygdala-dependent or fear-related learning. The consisted of two open arms, surrounded by a short edge to prevent falls, and two enclosed arms erected so that the two open arms were opposite each other. The maze was raised approximately 35 cm above the ground using a stable stand, and the arms of the maze were connected by a central platform. During the trials, each rat was gently placed on an open arm, positioned to face away from the central platform and the closed arms. The time it took the rats to retreat and move to the closed arms was recorded as the transfer latency. The principle of this experiment is primarily based on the aversion of rats to heights and open spaces [15].

Forced swim test (FST)

The forced swim test (FST) is one of the most used animal models for assessing antidepressant-like behavior. The transparent swim cylinder is filled with water (room temperature) to a depth of 30 cm (modified FST). Individual rats are then placed in the water in the swim cylinders, allowed to freely swim within a time limit of 3 minutes, and recorded with an attached video camera. After the 3-minute trials, the rats were removed from the water, towel-dried, and returned to their home cages. Twenty-four hours after the first trial, repeat the procedures above [24].

Elevated zero maze (EZM)

The maze was constructed of black acrylic in a circular track 10 cm wide, 105 cm in diameter, and elevated 72 cm from the floor. The maze was divided into four quadrants of equal length, with two opposing open quadrants with 1 cm high clear acrylic curbs to prevent falls, and two opposing closed quadrants with black acrylic walls 28 cm in height. A 5-minute period began with the animal placed in the center of a closed quadrant. The dependent measures were the same as those for the Plus, except for no center region. Between trials, the maze was cleaned with 70% ethanol [25].

Light and dark boxes

The light-dark box test (LDT) is one of rodents' most widely used tests to measure anxiety-like behavior. The test is based on the natural aversion of rodents to brightly illuminated areas and their spontaneous exploratory behavior in response to mild stressors, such as novel environments and light. This test is also sensitive to anxiolytic drug treatments. The test apparatus consisted of a box divided into a small (one-third) dark chamber and a large (two-thirds) bright chamber. Rats were placed into the lit compartment and allowed to move freely between the two chambers. The first latency to enter the dark compartment and the total time spent in the lit compartment are indices for bright-space anxiety in rats. Transitions are an index of activity-exploration, because of habituation over time. LDT is quick and easy to use, without requiring prior training of animals.

The apparatus for the light/dark transition test consisted of a box (42 x 21 x 25 cm) divided into a small (one-third) dark compartment and a large (two-thirds) illuminated compartment. A restricted opening 3 cm high and 4 cm wide connected the two chambers. Video camera (placed directly above apparatus).

The rats were allowed to freely explore the chambers for about five (5) minutes. The activities were recorded on video and later analyzed. The following parameters are scored: the latency time to enter the dark compartment, the time spent in the light/dark compartment, the distance travelled in the light chamber, and the number of transitions.

Morris water maze test

The Morris water maze test is a test for spatial learning (including long-term memory [LTM], short-term memory [STM]) in animals. The apparatus consisted of a circular pool (250 cm diameter, 60 cm deep at the side) filled with water at 25°C ± 1°C, stained with milk to a depth of 20 cm. An invisible escape platform (10 cm diameter) was placed in the middle of one of the quadrants (2 cm below the water surface) equidistant from the side wall and the middle of the pool. The room had numerous extra-maze cues that remained constant throughout the experiment and no intra-maze cues to ensure that the rats had to rely on the location of extra-maze cues to locate the platform. The procedure included training (without milk) and test sessions. The maze was divided into four imaginary quadrants, and a submerged Perspex platform (13 ± 13 cm) was placed in the middle of one quadrant for all training trials. The animals faced the wall when placed into the maze, with four starting positions (NE, NW, SE, and SW). Each animal was trained for four trials per day with inter-trial intervals of 20 minutes for two days (19th-20th day). Animals were allowed to swim until they found the hidden platform and stayed there for 20s before being picked up. The animal that failed to find the hidden platform in 60s was guided to it, allowed to stay there for 20s, and then returned to its heated cage after completing the task. The time required to reach the platform (escape latency) was recorded using a stopwatch. The measures were averaged per rat for each daily session [26, 15].

Spatial learning in the animals was tested by comparing the first exposure of the animals to water containing a platform and the second and third exposures the following day. The animals were first exposed to a water bath without milk, and the time it took the animal to get to the platform was recorded. The following day's exposure to a water bath with milk was to prove if the animal still recalls the previous exercise (first trial)–LTM, and the two other trials that were performed on the same day were to show if the animals still remember the exercise within the interval of couple of minutes STM. The reference memory- percentage time in platform quadrants was also observed.

Animal sacrifice and sample collection

About twenty-four (24) hours after the last experimental procedure, three (3) Wistar rats were randomly selected from each group. They were administered 20 mg/kg of ketamine to immobilize the rats and block sensations. The thoracic cage was exposed, blood was collected from the heart through the right atrium, and the heart was perfused with normal saline and neutral-buffered formalin to achieve whole-body perfusion fixation. The brains were collected and placed in a sample bottle filled with 15 mL of neutral buffered formalin for histology. Quick and rapid decapitation was performed in five (5) other rats to collect the brain for biochemical analysis. The brains of these rats were first immersed in normal saline, weighed, and then immersed in a cold 30% sucrose solution.

Biochemical evaluations

The biochemical markers evaluated included nitric oxide (NO), inducible NO, and AChE.

After the rats were anesthetized with ketamine and perfused with neutral buffered formalin, the brains were removed and emersed into a cold 30% sucrose solution. The brains were then homogenized and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 minutes, and the serum was collected into tubes containing the compounds for analysis.

NO level in the homogenized brain was measured using a colorimetric assay. This involves the conversion of nitrate to nitrite via nitrate reductase. Then the nitrite is converted to a purple azo compound using Griess reagent. The result is read using a spectrophotometer and is expressed as µg/m.

Inducible NO synthase activity was measured by adding 100 μL of supernatant to reaction mixture containing HEPES, 20.0 mmol/L (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM L-arginine (Sigma) and two mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) (Sigma) in a total volume of 0.5 mL and then incubated under constant air bubbling (1 mL/min) at 37°C for 120 minutes. The blank sample contained all reaction components except NADPH. Inducible NO synthase activity was calculated as the difference between the sample and blank readings. It was expressed as pg/mL.

AChE activity was measured using dithio-bisnitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) to measure the amount of thiocholine produced as acetylthiocholine hydrolyzed by AChE. The color of the DTNB adduct was measured using a spectrophotometer at 412 nm. AChE activity was expressed asµmol ASSC h/h/mg protein [27].

Statistical analysis

The data recorded in this study were reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Behavioral and biochemical data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and any in-group analysis was subjected to Bonferroni post-hoc test. P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The GraphPad software package was used for data analysis and graphical representation of the data.

Results

Changes in brain cholinergic and monoaminergic activities following dichlorvos (DDVP) exposure and atropine and citric acid interventions

The results of acetylcholine levels showed higher AChE levels in the brain of the untreated DDVP-exposed rats, comparable to what was recorded in all the intervention groups, except the DDVP plus citric acid group, where a considerably higher AChE was recorded (Figure 1A). DDVP exposure reduced acetylcholine (Ach) levels, and only interventional or single ingestions of atropine resulted in a comparable increase in Ach in the brains of the exposed rats (Figure 1C). Notably, brain ACh levels in the atropine-treated groups further confirmed its cholinergic activity under physiological and pathological conditions.

Repeated DDVP ingestions caused a considerable increase in the activities of monoamine oxidases (MAO) in the brains of the poisoned rats, which consequently led to a marked reduction in the serotonin (5HT) levels in the brains of the rats (Fig. 1B and D). Interestingly, both atropine and citric acid, either as a single drug or in combination, in their interventional ingestions in DDVP-exposed rats reduced MAO activities and improved serotonin concentrations (Fig. 1B and D).

Figure 1. Graphical Representation Showing the Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Activities (A), Monoamine Oxidases (MAO) Levels (B), Acetylcholine (Ach) Levels (C), and Serotonin Levels in the Brains of Wistar Rats Exposed to Normal Saline (Control), Dichlorvos (DDVP), and Interventions or Control Ingestions of Atropine and Citric Acid. Asterisk (*, **, ***) indicates statistically significant differences. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), one-way ANOVA.

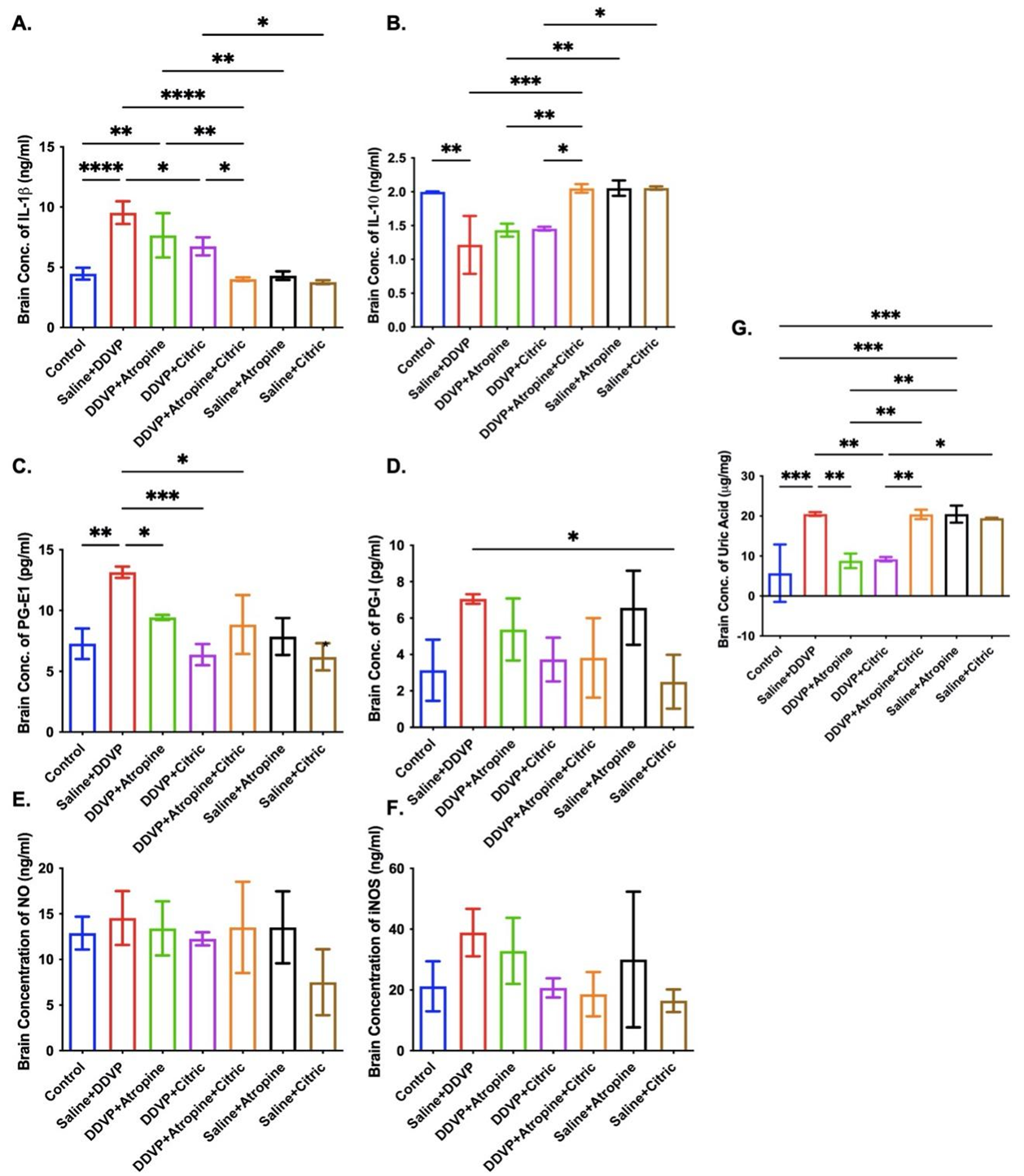

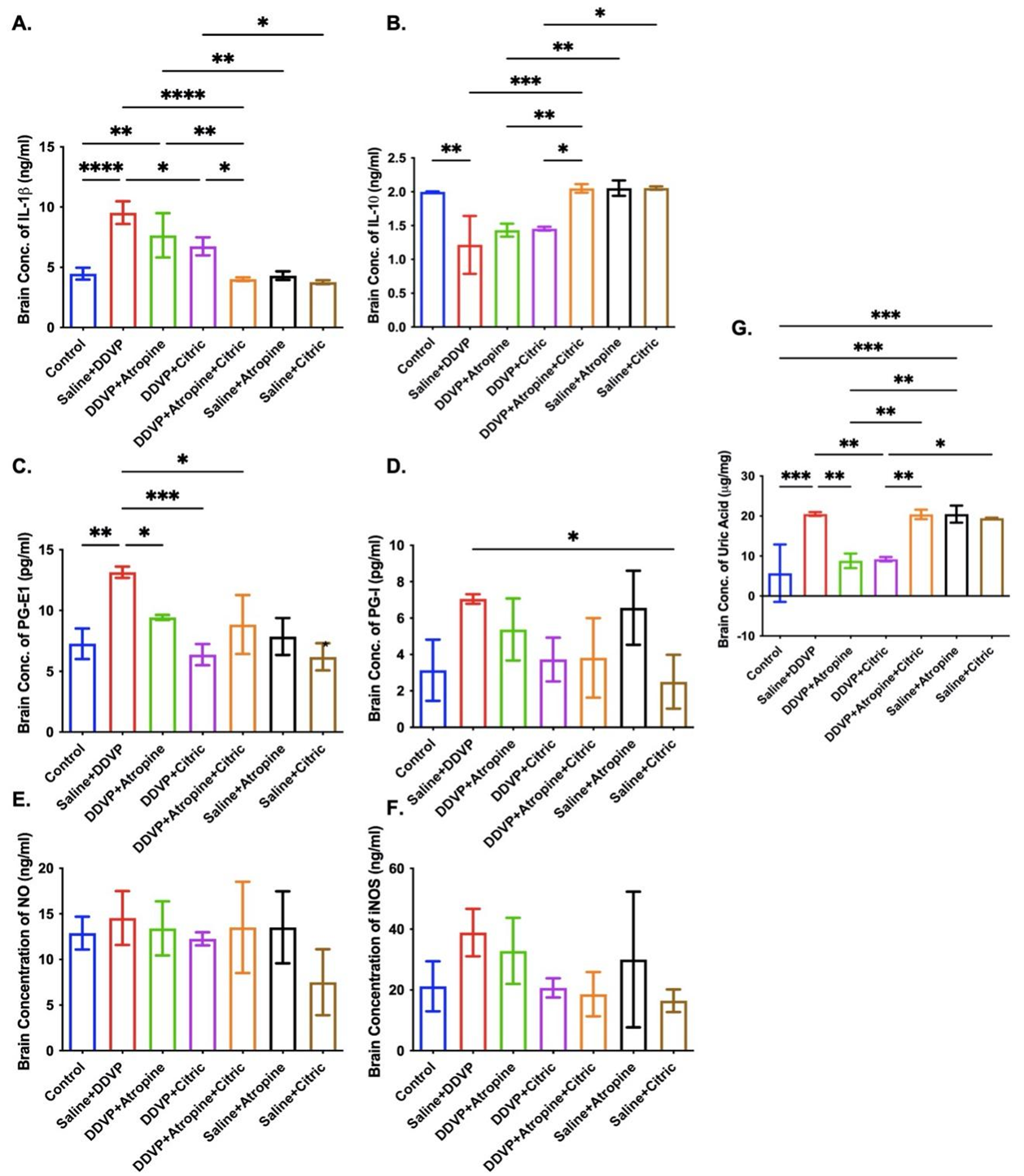

Inflammatory, oxidative stress and cytotoxic biomolecules in the brain following dichlorvos (DDVP) exposure and atropine and citric acid interventions

Repeated DDVP exposure resulted in a significantly (P ≤ 0.05) high concentration of IL-1b in the brains of the untreated poisoned rats (Fig. 2A). Interventional treatment with citric acid, atropine, and their combinations significantly (P ≤ 0.05) reduced IL-1b concentrations of the brain of the DDVP-poisoned and non-poisoned rats, although citric acid appeared to cause more reductions (Figure 2A). This marked depletion of the IL-1b concentrations in the brains of the treated rats suggests that citric acid complemented the anti-inflammatory capacity of atropine in the DDVP-poisoned rats.

Strengthening the pro-inflammatory effects of DDVP poisoning is the significantly lower concentration of IL-10 in the poisoned rats, indicating that DDVP may promote inflammation and prevent anti-inflammation in insecticide poisoning (Fig. 2B). In contradiction to the atropine's effects on IL-1b is that atropine is unable to promote increased concentration of IL-10 in the poisoned rats, even though it improved it in the non-poisoned atropine-treated rats (Fig. 2B). Citric acid, on the other hand, promoted an increased concentration of IL-10 in the DDVP-poisoned and non-poisoned rats’ brain, either as a stand-alone drug or in combination with atropine (Fig. 2B).

Poison-like repeated oral ingestions of DDVP caused a significant (P ≤ 0.05) increase in prostaglandin (PG)-I and PG-E1 activities in the brains of the exposed rats (Fig. 2C and D). Atropine ingestion after DDVP poisoning caused relative reduction in PG-I and PG-E1 activities, while citric acid, either in its interventional strategy or as an experimental control, caused more marked and significant depletions (P ≤ 0.05) in the activities of both poisoned and non-poisoned rats' brains (Fig. 2C and D). Citric acid supplementation with atropine in DDVP-poisoned rats resulted in a more obvious inhibition of PG-I and PG-E1 activities in the brains of the poisoned rats compared to the rats treated with atropine alone (Fig. 2C and D).

The level of oxidative stress associated with neuroinflammation and cytotoxicity in the brain was measured using NO and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) markers, respectively. The effect of NO is directly proportional to the amount of oxidative stress. DDVP-poisoning in rats caused marked production of both NO and iNOS in the brain, with more effects on the generation of iNOS, suggesting that DDVP may cause insult-driven (cytotoxicity) oxido-inflammation (Fig. 2E and F). Expectedly, citric acid ingestions, either as a stand-alone drug or a supplement, caused more significant depletion in NO and iNOS concentrations in the brains of both poisoned and non-poisoned rats (Fig. 2E and F).

Uric acid overproduction can be associated with neurotoxicity driven by inflammation or oxidative stress. Here, DDVP poisoning is observed to cause a significant (P ≤ 0.05) increase in the brain concentration of uric acid in the DDVP-untreated rats. In contrast, citric acid and atropine ingestion caused relatively lower concentrations of uric acid in DDVP-poisoned rats, but not in non-poisoned rats (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2. Graphical Representation Showing the Concentrations of Interleukin (IL)-1b (A), IL-10 (B), Prostaglandin (PG)-E1 (C), PG-I (D), Nitric Oxide (NO) (E), Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) (F) and Uric Acid (G) in the Brains of Wistar Rats Exposed to Normal Saline (Control), DDVP, and Interventions or Control Ingestions of Atropine and Citric Acid. Asterisk (*, **, ***) indicates statistically significant differences. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA.

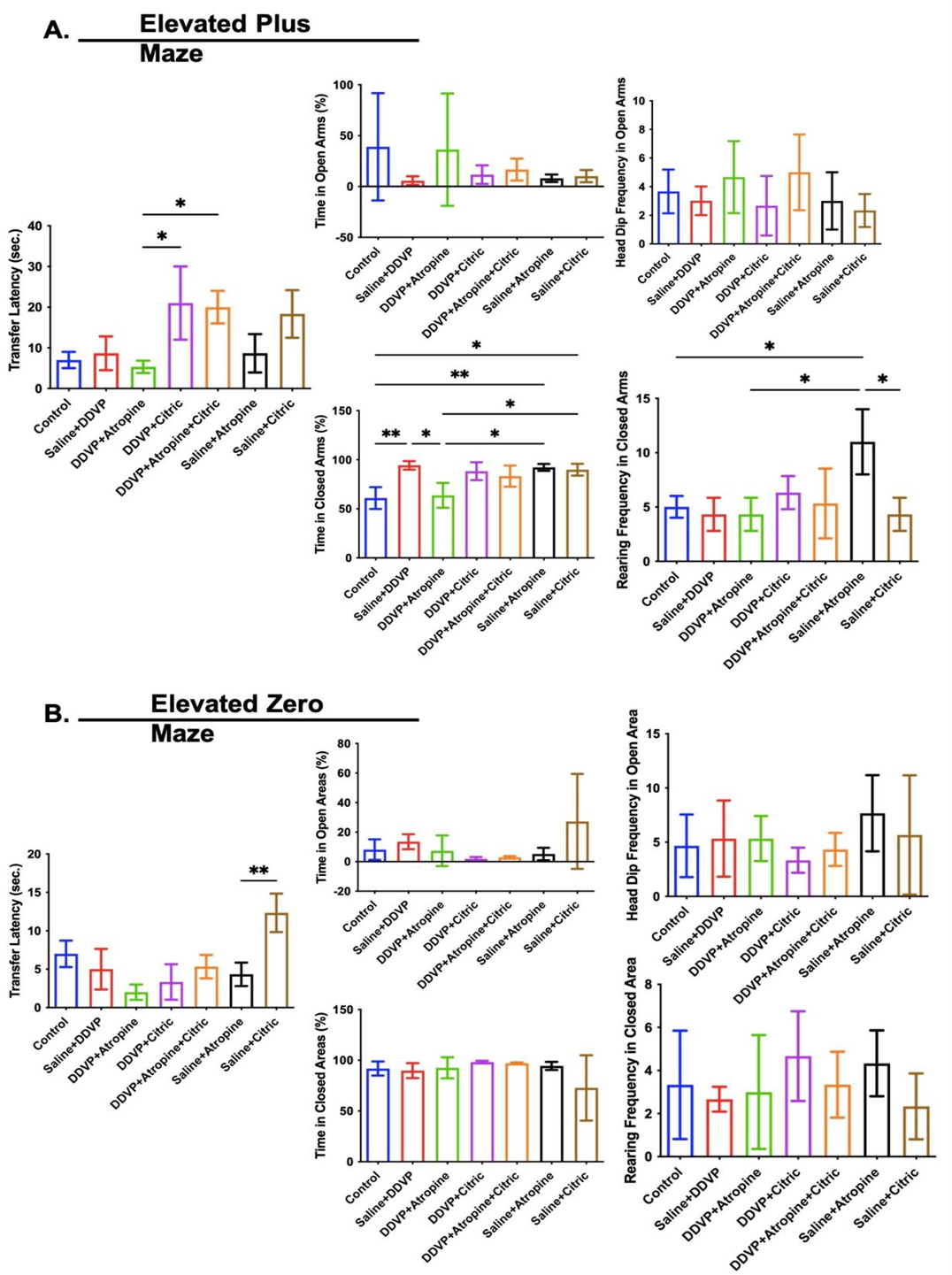

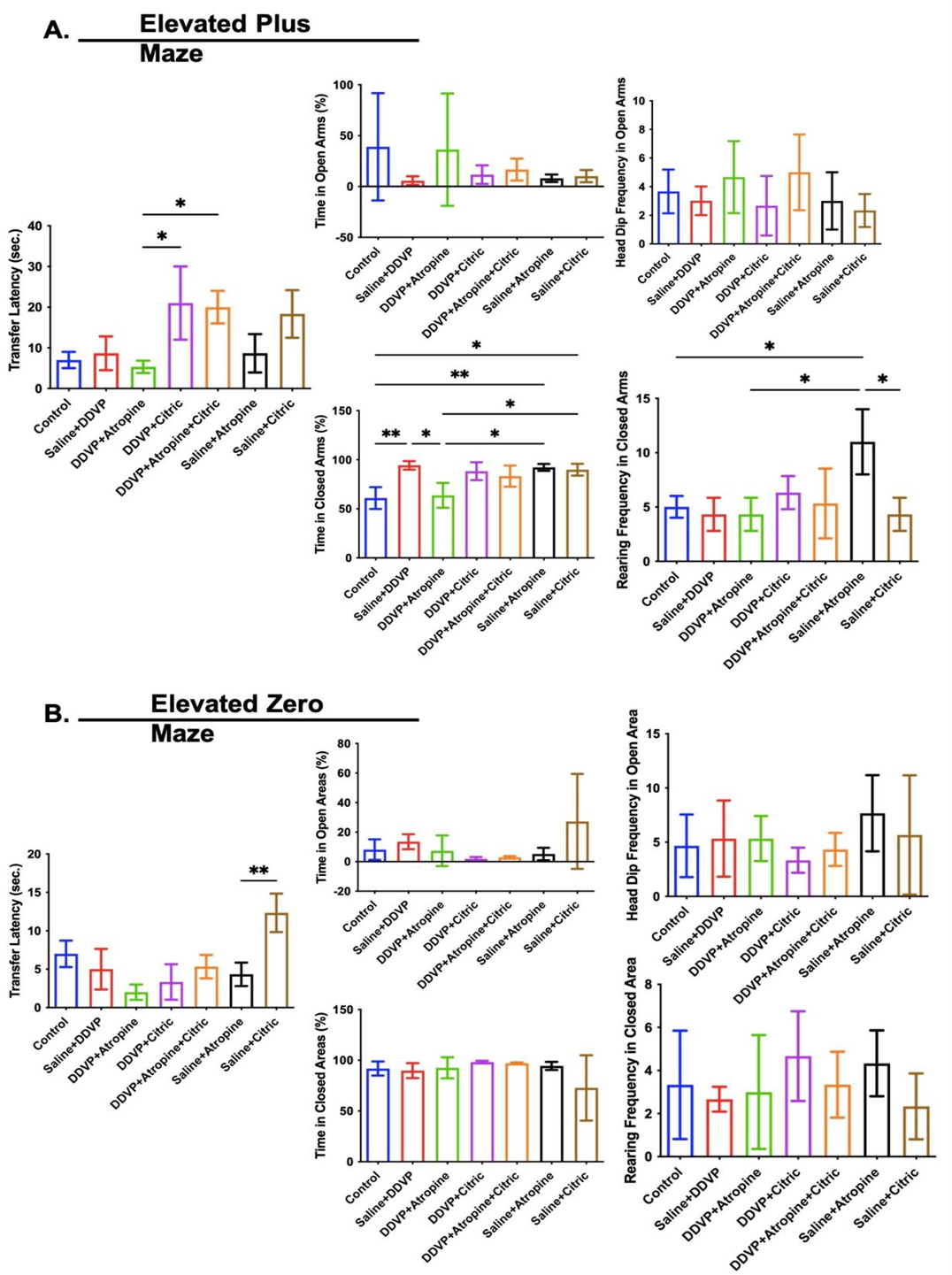

Exploratory-like, anxiety-related behaviours in following dichlorvos (DDVP) exposure and atropin-citric acid interventions

Exploratory behaviours are motor-related activities used to measure physical activity and environmental awareness in laboratory rodents. In this study, upright/vertical body extensions, called rearing behaviours and horizontal explorations, were measured as head dip frequencies and rearing frequencies in the EPM (Figure 3A) and elevated zero maze (EZM) (Figure 3B), respectively. Horizontal explorations (head dip frequencies) were not affected by repeated DDVP exposure or interventional ingestions of atropine and citric acid in either the EPM (Figure 3A) or EZM (Figure 3B). Contrary to this observation, rearing frequencies were slightly reduced by DDVP exposure, most notably in the EZM, and only the interventional treatment or singular ingestions of atropine consistently improved rearing frequencies in EPM and EZM (Figure 3A and B).

The time to avoid the open area and seek cover (transfer latency) and the time in the open and closed arms were the indices of anxiety-related behaviors assessed here (Figures 3A and B). In the EPM, DDVP exposure had little to no effect on the transfer latency and time in the open arms, but caused the rats to spend more time in the closed arms, which is a sign of anxiety in rodents (Figure 3A). Consequently, interventional treatments with citric acid, not with atropine caused an increase in transfer latency in the EPM, while neither agents reduced the time spent by the rats in the closed arms as a result of DDVP exposure (Figure 3A). Unlike in the EPM, DDVP exposure and interventional or singular ingestion of atropine, and citric acid did not affect the transfer latency, time in the open area, and time in the closed areas in the EZM (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Graphical Representation Showing the Anxiety-Like and Exploratory Behaviours in the Elevated Plus Maze (A) and Elevated Zero Maze (A) in Wistar Rats Exposed to Normal Saline (Control), Dichlorvos (DDVP), and Interventions or Control Ingestions of Atropine and Citric Acid. Asterisk (*, **) indicates statistically significant differences. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA.

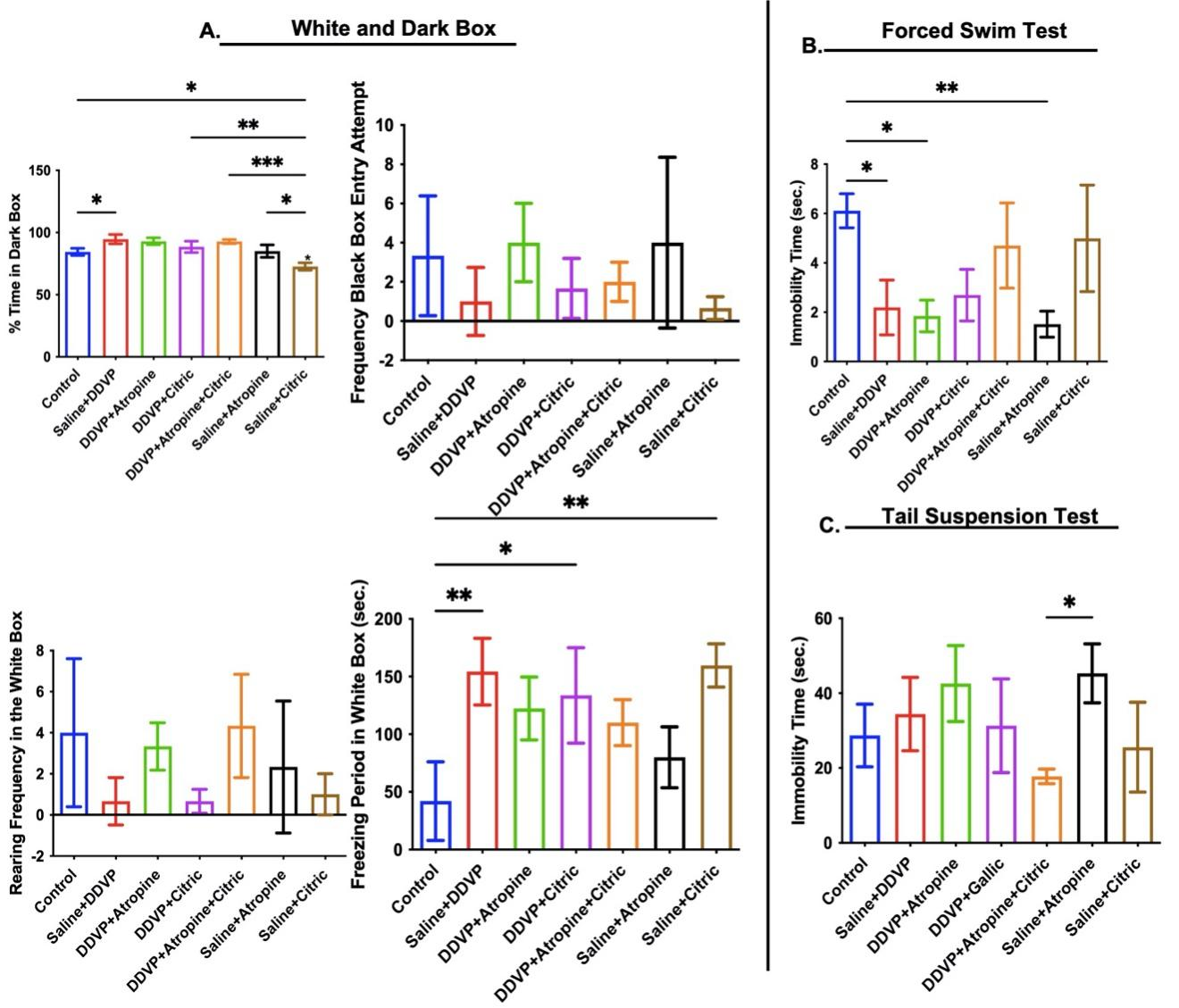

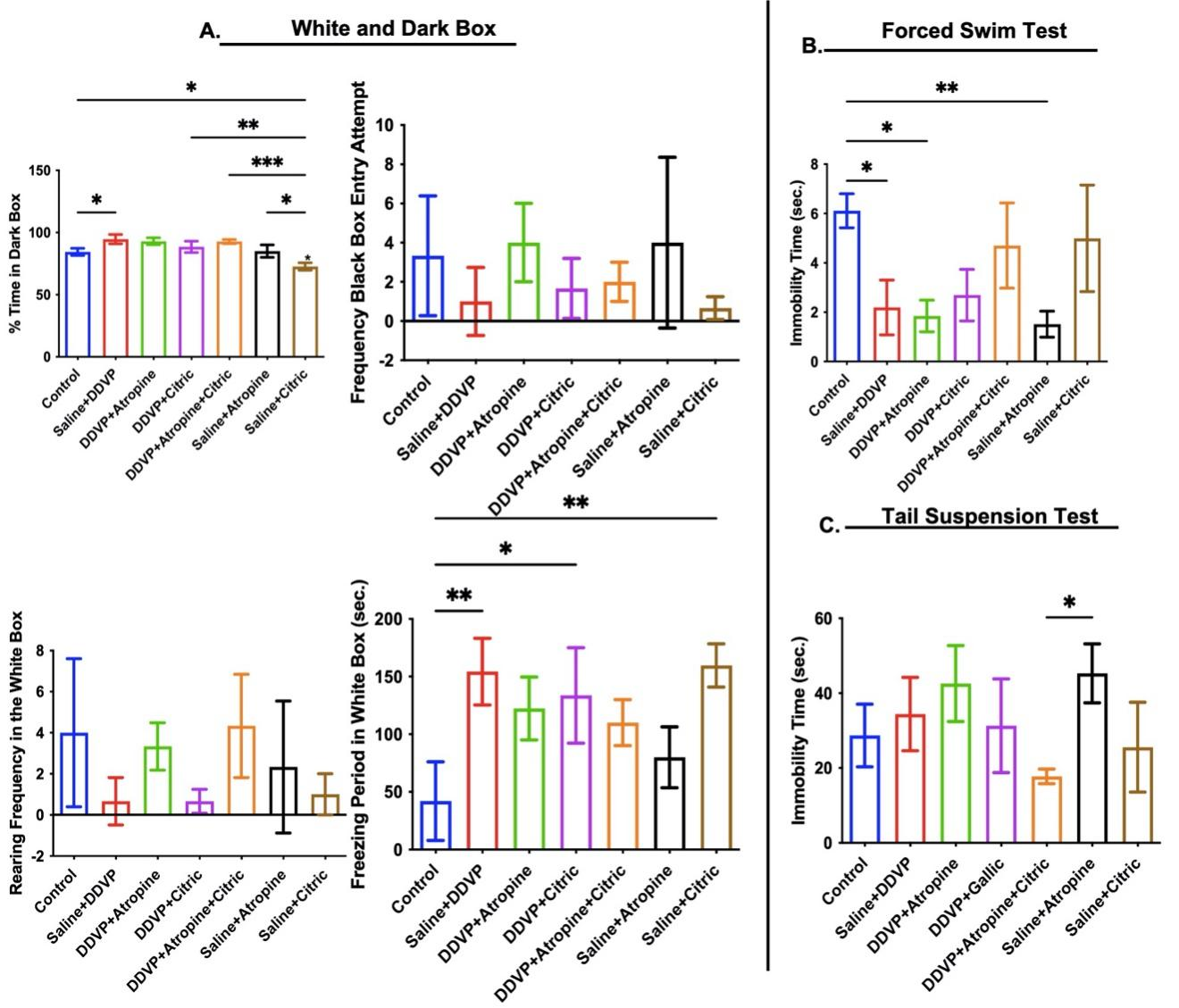

Anxiety and depressive-like behaviours following dichlorvos (DDVP) exposure and atropin-citric acid interventions

Anxiety-like behaviours measured in the white and dark box paradigm appeared to be affected by DDVP poisoning; there was a significant increase in time spent in the dark box and freezing period in the white box in DDVP-exposed rats (Figure 4A). Interventional treatments with comparable citric-atropine ingestions reduced freezing period and time spent in the dark box (Figure 4A). However, DDVP exposure significantly reduced immobility time in the FST but increased it the tail suspension test (Figure 4B and C). Citric acid interventions, either as a single drug or in combination, but not atropine, reversed the differential depressive-like activities observed in untreated DDVP-poisoned rats (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4. Graphical Representation Showing the Anxiety-Like Behaviors in the White and Dark Box (A) and Depressive-Like Behaviors in the Forced Swim Test (B) and Tail Suspension Test (C) in Wistar Rats Exposed to Normal Saline (Control), Dichlorvos (DDVP), and Interventions or Control Ingestions of Atropine and Citric Acid. Asterisk (*, **, ***) indicates statistically significant differences. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA.

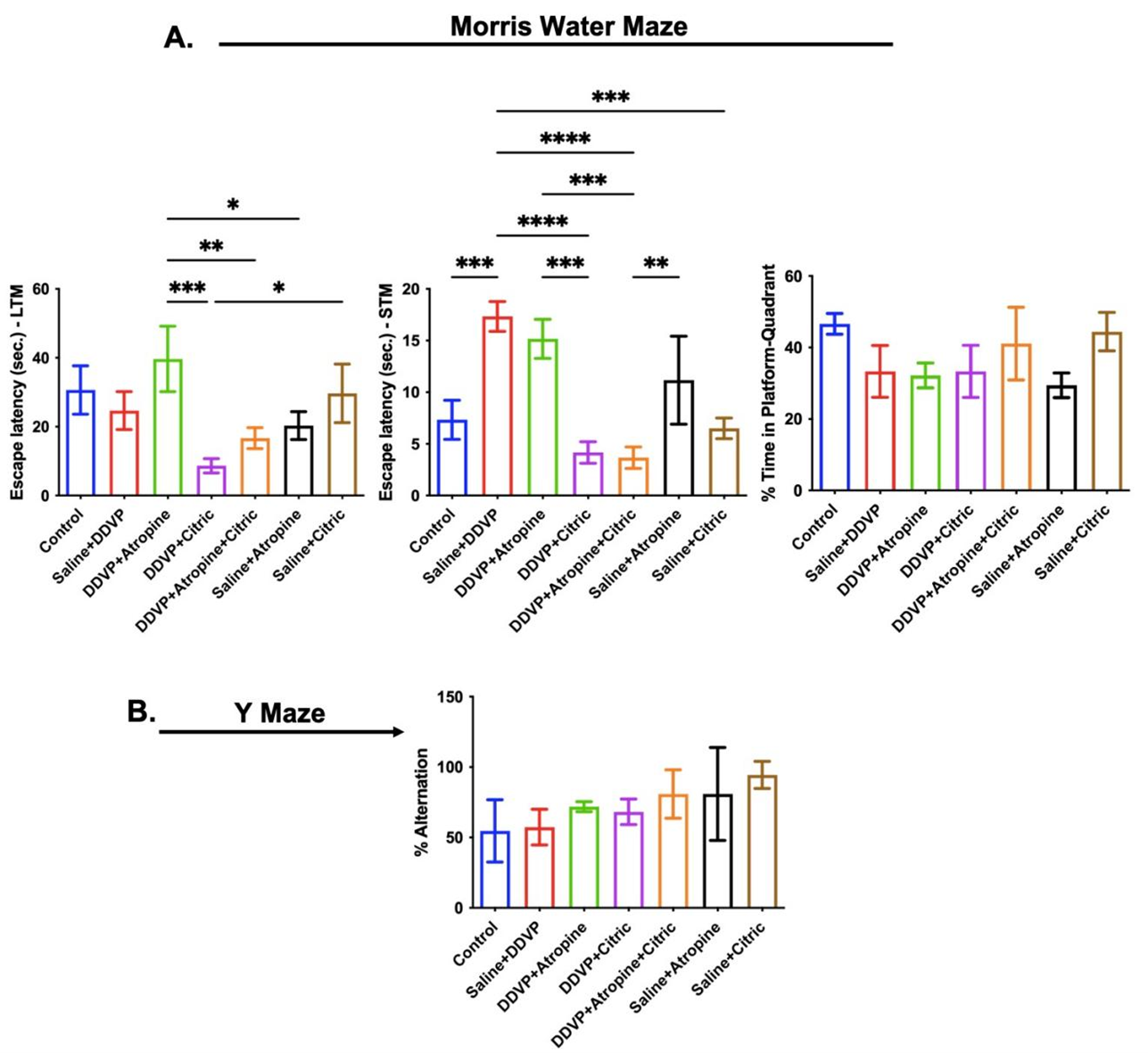

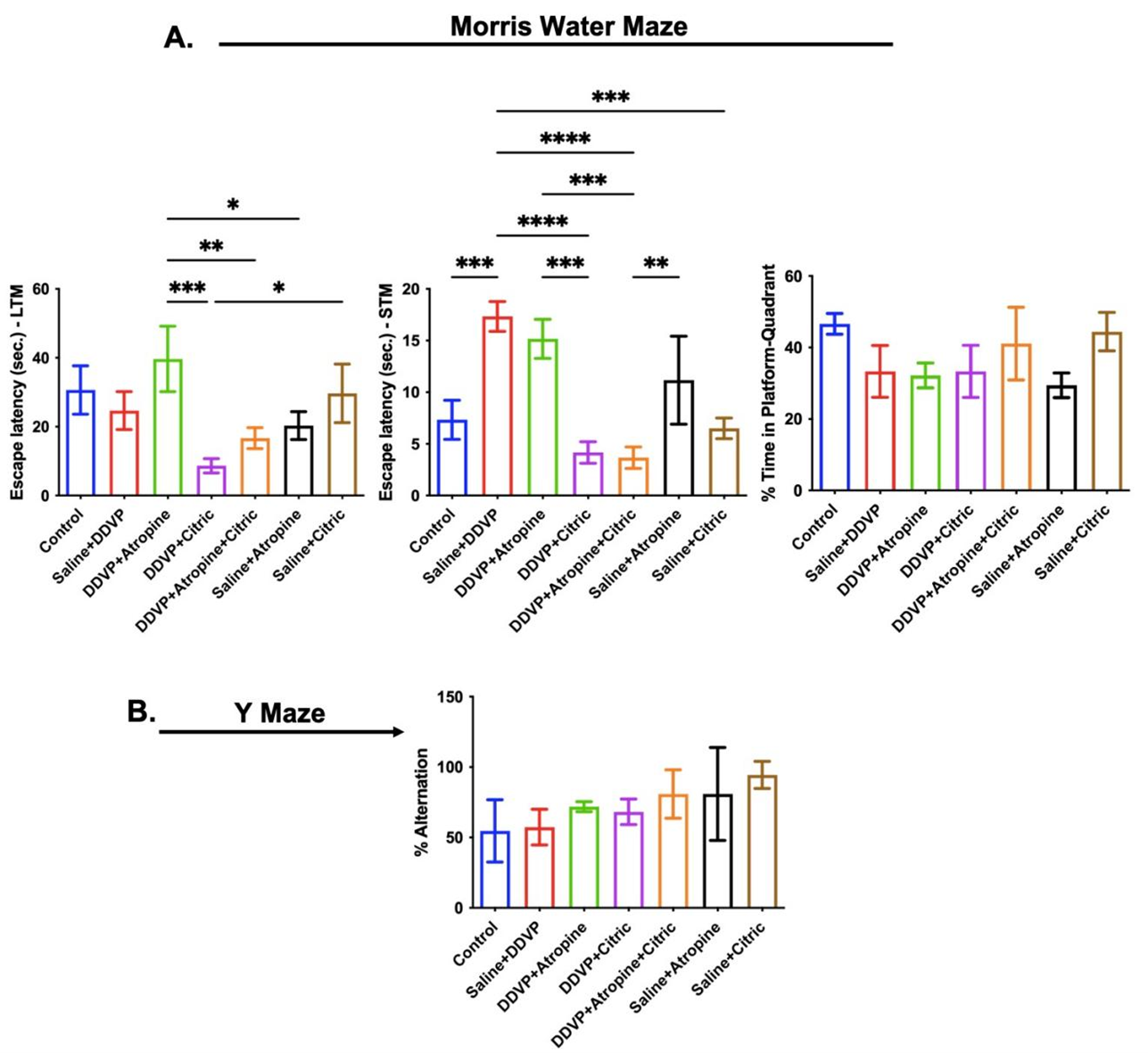

Spatial memory behaviours following dichlorvos (DDVP) exposure and atropin-citric acid interventions

Spatially associated memory phenotypes were assessed using the Morris water maze and Y maze paradigms. Poisoning-like repeated oral ingestions of DDVP caused a significant delay in finding the hidden platform, recorded as high escape latency during the STM trials (Figure 5A – STM), but not in the LTM) trials (Figure 5A – LTM). In line with the effects on STM, DDVP poisoning led to a consequential loss of reference memory, evidenced in the reduced time the exposed rats spent around the quadrant that previously contained the hidden platform (Figure 5A). Unexpectedly, atropine alone interventions further delayed escape latencies in the STM and LTM trials, reducing the time spent in the quadrant previously containing the platform (Figure 5A). Interestingly, interventional ingestions of citric acid, as a single dose, or in supplementary dosage with atropine, led to reduced escape latencies in both STM and LTM trials and increased time around the platform quadrant (Figure 5A).

Lastly, the spatial memory test in the Y maze paradigm revealed that DDVP exposure in the present study did not affect the percentage alternations, and both atropine and citric acid, either as a single agent or in combination, led to an increase in the percentage alternations (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Graphical Representation Showing the Spatial Working Memory Behaviors in the Morris Water Maze (A) and Y Maze (B) Paradigms in Wistar Rats Exposed to Normal Saline (Control), Dichlorvos (DDVP), and Interventions or Control Ingestions of Atropine and Citric Acid. Asterisk (*, **, ***, ****) indicates statistically significant differences. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

The widespread use of pesticides has serious health effects on both humans and animals [2]. Various clinical reports indicate the consequential neuro-cognitive effects of poisoning due to insecticide exposure [28], with specific reports of depression, loss of memory, and other psychological implications, including suicide [29].

AChE activity is the most commonly used biomarker for organophosphate poisoning [7]. Acetylcholine released from cholinergic nerve terminals is disposed of solely through hydrolysis by AChE [30], and this remains a crucial homeostatic function, essentially to regulate cholinergic activities. As expected, DDVP, an organophosphate, inhibited AChE activities, but not a proportional increase in ACh concentrations in the brain. An antioxidant citric acid as a sole drug resulted in AChE reactivation-like capacity, as it preserved the concentration of AChE compared to the naïve control. Although this may be far from a realistic and mechanistic point, this finding may be associated with the neuroprotective effects of citric acid.

It has been established previously that the mechanism of neurotoxicity following DDVP poisoning is not only via ChE inhibition [15]. Oxidative stress contributes to the consequential long-term effects of OPs. iNOS, which catalyzes the production of NO from L-arginine, plays crucial roles in some physiological regulation, inflammation, infection, and in the onset and progression of malignant diseases. iNOS is also a mediator of nonspecific host defense. However, excess production of NO is linked to tissue damage and organ dysfunction by inducing oxidative stress and cytotoxicity [31].

High levels of NO and iNOS and increased activities were associated with DDVP exposures, implying induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity. These observations infer a vital role for NO in developing DDVP neurotoxicity. The gaseous molecule NO has a crucial role in the brain as an intracellular messenger and in maintaining vascular tone owing to its vasodilator action [32]. Excess formation of NO in inflammatory and toxic states from astrocytes and microglia by the iNOS in the brain tissue can lead to neuronal death, and the increased activation of neuronal NO synthase during certain pathological conditions can result in the release of excessive amounts of NO, resulting in neurotoxicity [33]. NO itself is relatively non-toxic, but can react with oxygen to yield NO2 and N2O3, capable of inducing oxidative stress and DNA damage [34]. Energy depletion occurs because of an inhibitory action on cytochrome oxidase, mitochondrial respiration, glycolysis, and the induction of mitochondrial permeability transition [27]. Expectedly, the antioxidant capacity of the therapeutic targeted oral citric acid in the DDVP-poisoned rat caused marked depletions in both NO and iNOS, confirming further that citric acid supplementation may beneficially reverse or prevent the secondary cytotoxicity in DDVP poisoning [27].

The Morris water maze test was used to assess the animals' spatial learning memory, including LTM, STM, and reference memory. This spatial learning task involves the activities of hippocampal N-Methyl-D-Aspartate and Muscarinic cholinergic receptors [26]. Repeated oral ingestion of DDVP increased the escape latency of all animals, with varying levels of difficulty in remembering the previous exercises. This result is not unrelated to what is previously reported for some OPs, which caused inhibition of the activities of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate and Muscarinic cholinergic receptors, inducing alterations in mitochondrial dynamics, such as increased mitochondrial length and reduced number of mitochondria, and impaired axonal transport in the hippocampus [35]. Because it took a while to remember where the escape platform was, the time they spent in the quadrant housing the platform was also minimal, suggesting that their performance in the reference memory tasks is heavily related to the outcome of the STM trials.

Meanwhile, interventional ingestions of citric acid, as a single dose or supplementary, after initial exposures to DDVP, improved all indices of spatial memory functions, including short-term, long-term, reference, and working memory. This finding is comparable to the effects of citric acid on the hippocampal cellular integrity and memory functions in aluminum-poisoned mice [36].

In this study, DDVP induced anxiety and fear-like behaviours in animals treated [37] as observed in the increased time spent in the dark box in the light-box test, reduced number of head dips in the open arms, increased time spent in the closed arms, reduced rearing frequency in closed arms, and longer transfer latency in EPM. Likewise, in the results of EZM, where animals were treated with DDVP, an increased head dip frequency was observed in the open area, reduced time spent in the closed area, reduced rearing frequency in the closed area, and increased transfer latency in EZM. Regarding the immobility time shown in FST, animals treated with DDVP had a significantly reduced immobility time. This indicates that DDVP has induced anxiety-like behaviors in the animals, which is similar to the work carried out by [15].

In animals treated with citric acid alone after exposure to DDVP, there was significant ameliorative evidence in the behavioral parameters. This observation was made based on the reduced time spent in the dark box in the light and dark box test, decreased time spent in closed arms, and higher rearing frequency in closed arms. This was also observed in animals treated with DDVP and atropine. Those treated with DDVP, atropine and citric acid showed a significant increase in head dip frequency in the open arms and rearing frequency. Ameliorative evidence in behavioral parameters was also observed in the immobility time of animals treated with atropine and citric acid, in which there was a significant increase in immobility time. Ameliorative evidence in behavioral parameters was also observed in animals treated with DDVP and citric acid, and animals treated with DDVP, atropine, and citric acid in which a significant decrease was observed in head dip frequency in the open area, compared to those treated with DDVP and atropine, which showed an increase in head dip frequency for EZM. Ameliorative evidence was observed in animals treated with DDVP and atropine, DDVP and citric acid, and those treated with DDVP, atropine, and citric acid, which showed a significant increase in rearing frequency in a closed area in the EZM. Ameliorative evidences were observed in animals treated with DDVP and citric acid, DDVP and atropine, and those treated with DDVP, atropine and citric acid, showing an increase in time spent in the closed area. Animals treated with DDVP and atropine, DDVP and citric acid, and DDVP, atropine, and citric acid all showed ameliorative effects in reduction in transfer latency, in which animals treated with DDVP and atropine had more reduction. These are supported by the relative neurocognitive deficits caused by exposures to different types of insecticide compounds including organophosphate [15].

As a consequential implication of the induced oxidative stress and impaired cholinergic functions, DDVP causes significant depletion of 5-HT concentration, similar to the finding of reduced 5-HT concentrations after DDVP exposure. Although, according to the work of the toxic effect of DDVP on serotonin is uncertain. Low serotonin level has been related to cognitive deficits observed in Alzheimer's disease, and it is liable to contribute to cognitive age-related cognitive decline [38]. Memory impairment results from overstimulation of the serotonin receptor. Serotonergic dysfunction is considered a neuronal substrate of depression [39]. The above statements show that DDVP significantly reduces serotonin levels in the brain. Atropine blocks the action of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptor [40].

From the 5HT biochemical tests, it was observed that animals exposed to DVVP and then treated with atropine and citric acid showed an increased 5HT level in the brain. The administration of atropine as a treatment for rats exposed to DDVP showed no significant effect on the 5HT level in the brain. Upon co-administration of citric acid to the DDVP-treated animals, a significant ameliorative effect was observed on the 5HT level.

According to the results obtained from the MAO test, treatment with DDVP caused a significant increase in MAO activities. There are certain physiological conditions linked with the abnormal activity of MAOs; increased activity of MAOs is closely associated with chronic mental illnesses and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease [41]. MAO-mediated reactions give rise to several chemical species with likely neurotoxic properties, such as aldehydes and ammonia. Consequently, lengthy excessive activity of these enzymes may contribute to mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative disorders. Hydrogen peroxide, a neurotoxin, can activate the production of reactive oxygen species and induce mitochondrial damage and neuronal apoptosis. Oxidative stress contributes to MAO activity functions in a wide range of neuropsychiatric dysfunctions. Mitochondrial damage and deregulation of redox balance induced by MAO activation may cause neuronal apoptosis and brain damage [42]. The above statements support this study which shows that DDVP caused a significant increase in MAO activities of the brain.

As a tricarboxylic acid or Krebs cycle component, citric acid is found in all animal tissues as an intermediary substance in oxidative metabolism [19]. Studies indicated that citrate decreases lipid peroxidation and downregulates inflammation by reducing polymorphonuclear cell degranulation and attenuating the release of myeloperoxidase, elastase, IL-1b, and platelet factor [19]. In vitro, citrate improved endothelial function by reducing the proinflammatory markers and decreasing neutrophil diapedesis in hyperglycemia [43]. Moreover, citric acid has been shown to reduce hepatocellular injury evoked in rats [41]. Excessive production and secretion of IL-1β have been shown to produce highly detrimental effects in many inflammatory conditions [44].

IL-10 is a cytokine with potent anti-inflammatory properties; therefore, the presence of a substance that causes a decrease in this marker is toxic to health [25]. The administration of DDVP caused a reduced level of IL-10, indicating that it is harmful to have DDVP in the body system because its reduction effect on IL-10 would make the rats susceptible to inflammation. The administration of atropine and citric acid caused a significant increase in IL-10 levels, indicating that the presence of atropine and citric acid is beneficial because they both increase IL-10 levels in the body, which protects the rats from inflammation. It has been shown in a study that IL-10 prevents histological damage to the liver, kidneys, and lungs after organophosphate poisoning [45]. In this study, citric acid enhanced the anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 and also enhanced spatial working memory. This study proves that the addition of citric acid to the treatments administered in clinics to organophosphate poisoning patients would go a long way in ameliorating the neurotoxic effect of DDVP on the patient.

Regarding the spatial working memory, the increase in percentage alternation implies that spatial working memory is enhanced. According to this study, the presence of DDVP caused a decrease in percentage alternation, meaning the rate of exploring the arms of the maze was reduced. This implies that the neurotoxicity of DDVP may have affected the spatial working memory of the animals, while the administration of atropine and citric acid caused a significant rise in the percentage alternation, showing that the presence of atropine and citric acid acted as antidotes and helped the spatial working memory of the rats, thereby aiding the exploring frequency of the rats in the maze.

Taken together, the administration of DDVP caused a decrease in the head dip frequency, which means the rats were not curious to explore the paradigms, which may imply that the spatial working memory was impaired, thereby causing the rats to be depressed, while the presence of atropine and citric acid caused an increase in head dips compared to those with DDVP administration, implying that the rats were more curious. In this study, DDVP had a neurotoxic effect on the brain, resulting in impairment of spatial working memory and depression in rats, while atropine and citric acid had antidotal effects, thereby aiding spatial working memory and enhancing the curiosity of the rats. In another study on organophosphate pesticides, higher blood concentrations of DDVP during pregnancy were associated with poorer mental and motor development at 3 years, and greater postnatal exposure to OPs was associated with difficulties in memory, attention, motor tasks, behavior, and reaction time. Prenatal exposure to OPs was also associated with poorer mental development [46].

Conclusions

Various behavioral tests, including anxiety-related, exploratory, depressive-like, and spatial working memory tests, showed that interventional co-therapy with atropine and citric acid can effectively reverse the neurobehavioral and potential pathological consequences of the oxidative-inflammatory mechanisms of DDVP poisoning, thereby preventing long-term neurological sequelae.

Data Access and Responsibility

Data from this research are available upon request.

Ethical Considerations

The Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences granted ethical review and approval for this study on 21.04.2017, University of Ilorin, with reference number UIL/UERC/AN2074.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization and design of the study, definition of intellectual content, experimental studies, literature search, collection of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, editing, and submission of manuscript: I.A. and A.M.S;

Experimental studies, literature search, data collection and analysis, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript editing, and review and final approval of the version to be published: A.A.A., O.E.A., O.J.O., M.O.A., and O.R.A.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the interns in the NeuroTox Group, for their technical support during the behavioral tests, and the Ilorin Neuroscience Group for providing some of the tools used during the conduct of the experiments.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

- Yao R, Yao S, Ai T, Huang J, Liu Y, Sun J. Organophosphate pesticides and pyrethroids in farmland of the pearl river delta, China: regional residue, distributions and risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1017. [DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20021017] [PMID: 36673774]

- Ahmad MF, Ahmad FA, Alsayegh AA, Zeyaullah M, AlShahrani AM, et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e29128. [DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29128]

- Henao L, Tejedo M, Méndez J, Bernal MH. Effects of three organophosphorus insecticides on tropical anuran tadpoles: lethality and implications to motor activity. South Am J Herpetol. 2024;31(1):12-21. [DOI:10.2994/SAJH-D-21-00026.1]

- Zavuga R. Organophosphate poisoning temporal trends and spatial distribution, Uganda, 2017─ 2022. Research Square. 2024. [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3903010/v1]

- Huang M, Zeng L, Wang C, Zhou X, Peng Y, Shi C, et al. A comprehensive and quantitative comparison of organophosphate esters: Characteristics, applications, environmental occurrence, toxicity, and health risks. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 2024;55(5):310-333. [DOI:10.1080/10643389.2024.2406587]

- Costa LG. Organophosphorus compounds at 80: some old and new issues. Toxicol Sci. 2018;162(1):24-35. [DOI: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx266] [PMID: 29228398]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Figueiredo TH, de Araujo Furtado M, Pidoplichko VI, Braga MFM. Mechanisms of organophosphate toxicity and the role of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Toxics. 2023;11(10):866. [DOI: 10.3390/toxics11100866]

- Lenina OA, Zueva IV, Zobov VV, Semenov VE, Masson P, Petrov KA. Slow-binding reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase with long-lasting action for prophylaxis of organophosphate poisoning. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16611. [DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-73822-6] [PMID: 33024231]

- Yesilbas O, Kihtir HS, Altiti M, Petmezci MT, Balkaya S, Bursal Duramaz B, et al. Acute severe organophosphate poisoning in a child who was successfully treated with therapeutic plasma exchange, high‐volume hemodiafiltration, and lipid infusion. J Clin Apher. 2016;31(5):467-469. [DOI: 10.1002/jca.21417]

- Pang Z, Hu CM, Fang RH, Luk BT, Gao W, Wang F, et al. Detoxification of organophosphate poisoning using nanoparticle bioscavengers. ACS Nano. 2015;9(6):6450-6458. [DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02132] [PMID: 26053868]

- Katz KD, Brooks DE, Tarabar A, Kirkland L. Organophosphate toxicity clinical presentation. Medscape. 2018. [Link]

- Akamo AJ, Ojelabi AO, Somade OT, Kehinde IA, Taiwo AM, Olagunju BA, et al. Hesperidoside abolishes dichlorvos-mediated neurotoxicity in rats by suppressing oxidative stress, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and NF-κB-p65/p53/caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. Phytomedicine Plus. 2025; 4(1): 100701. [DOI:10.1016/j.phyplu.2024.100701]

- Udodi PS, Anonye TC, Ezejindu DN, Abugu JI, Omile CI, Obiesie IJ, et al. Exposure to insecticide mixture of cypermethrin and dichlorvos induced neurodegeneration by reducing antioxidant capacity in striatum. J Chem Health Risks. 2023;13(3): 423 - 439. [Link]

- Amaeze NH, Komolafe BO, Salako AF, Akagha KK, Briggs TD, Olatinwo OO, et al. Comparative assessment of the acute toxicity, haematological and genotoxic effects of ten commonly used pesticides on the African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus Burchell 1822. Heliyon. 2020; 6(8). [DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04768] [PMID: 32904247]

- Imam A, Sulaiman NA, Oyewole AL, Chengetanai S, Williams V, Ajibola MI, et al. Chlorpyrifos- and dichlorvos-induced oxidative and neurogenic damage elicits neuro-cognitive deficits and increases anxiety-like behavior in wild-type rats. Toxics. 2018;6(4):71. [DOI: 10.3390/toxics6040071]

- Bashyal B, Yadav A, Deo AK, Kharel KK, Kharel D, Panthi B. Severe acute organophosphate poisoning managed with 2-month prolonged atropine therapy: a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(10):5179-5182. [DOI: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001207]

- Kose A, Gunay N, Yildirim C, Tarakcioglu M, Sari I, Demiryurek AT. Cardiac damage in acute organophosphate poisoning in rats: effects of atropine and pralidoxime. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(2):169-75. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.01.016] [PMID: 19371524]

- Lambros M, Tran TH, Fei Q, Nicolaou M. Citric acid: a multifunctional pharmaceutical excipient. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):972. [DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14050972]

- Wu X, Dai H, Liu L, Xu C, Yin Y, Yi J, et al. Citrate reduced oxidative damage in stem cells by regulating cellular redox signaling pathways and represent a potential treatment for oxidative stress-induced diseases. Redox Biol. 2019;21:101057. [DOI: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.015]

- Infantino V, Pierri CL, Iacobazzi V. Metabolic routes in inflammation: the citrate pathway and its potential as therapeutic target. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(40):7104-7116. [DOI: 10.2174/0929867325666180510124558]

- Zotta A, Zaslona Z, O’Neill LA. Is citrate a critical signal in immunity and inflammation?. J Cell Signaling. 2020;1(3). [DOI:10.33696/Signaling.1.017]

- Bukunmi Ogunro O. Redox-regulation and anti-inflammatory system activation by quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside-rich fraction from Spondias mombin leaves: biochemical, reproductive and histological study in rat model of dichlorvos toxicity. RPS Pharm Pharmacol Rep. 2023;2(2):rqad016. [DOI:10.1093/rpsppr/rqad016]

- Liu Y, Zhang Z, Yang C, Li M, Yu Z, Xiaoguang C, et al. Influence of citric acid on aluminum-induced neurotoxicity in ca3 and dentate gyrus regions of mice hippocampus. Fresenius Environ Bulletin. 2013;22(2):474-479. [Link]

- Smalheiser NR, Graetz EE, Yu Z, Wang J. Effect size, sample size and power of forced swim test assays in mice: Guidelines for investigators to optimize reproducibility. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0243668. [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243668] [PMID: 33626103]

- Patilas C, Varsamos I, Galanis A, Vavourakis M, Zachariou D, Marougklianis V, et al. The role of interleukin-10 in the pathogenesis and treatment of a spinal cord injury. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024;14(2):151. [DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics14020151]

- Abdulmajeed WI, Sulieman HB, Zubayr MO, Imam A, Amin A, Biliaminu SA, et al. Honey prevents neurobehavioural deficit and oxidative stress induced by lead acetate exposure in male Wistar rats- a preliminary study. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31(1):37–44. [DOI: 10.1007/s11011-015-9733-6]

- Abdel-Salam OM, Youness ER, Mohammed NA, Yassen NN, Khadrawy YA, El-Toukhy SE, et al. Novel neuroprotective and hepatoprotective effects of citric acid in acute malathion intoxication. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(12):1181-1194. [DOI: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.11.005] [PMID: 27955746]

- Zou S, Wang Q, He Q, Liu G, Song J, Li J, et al. Brain-targeted nanoreactors prevent the development of organophosphate-induced delayed neurological damage. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023; 21:256. [DOI: 10.1186/s12951-023-02039-2] [PMID: 37550745]

- Eddleston M, Buckley NA, Eyer P, Dawson AH. Management of acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):597-607. [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61202-1] [PMID: 17706760]

- Colović MB, Krstić DZ, Lazarević-Pašti TD, Bondžić AM, Vasić VM. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11(3):315–335. [DOI: 10.2174/1570159X11311030006] [PMID: 24179466]

- Beheshti F, Hashemzehi M, Hosseini M, Marefati N, Memarpour S. Inducible nitric oxide synthase plays a role in depression- and anxiety-like behaviors chronically induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats: Evidence from inflammation and oxidative stress. Behav Brain Res. 2020;392:112720. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112720]

- Picón-Pagès P, Garcia-Buendia J, Muñoz FJ. Functions and dysfunctions of nitric oxide in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865(8):1949-1967. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.11.007] [PMID: 30500433]

- Tewari D, Sah AN, Bawari S, Nabavi SF, Dehpour AR, Shirooie S, et al. Role of nitric oxide in neurodegeneration: function, regulation, and inhibition. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(2):114–126. [DOI: 10.2174/1570159X18666200429001549]

- Sobrevia L, Ooi L, Ryan S, Steinert JR. Nitric oxide: a regulator of cellular function in health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:9782346. [DOI: 10.1155/2016/9782346] [PMID: 26798429]

- Kolić D, Kovarik Z. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors: Structure, function, and role in organophosphorus compound poisoning. Biofactors (Oxford, England). 2024;50(5):868–884. [DOI: 10.1002/biof.2048]

- Kim J, Kang H, Lee YB, Lee B, Lee D. A quantitative analysis of spontaneous alternation behaviors on a Y-maze reveals adverse effects of acute social isolation on spatial working memory. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):14722. [DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-41996-4] [PMID: 37679447]

- Ommati MM, Nozhat Z, Sabouri S, Kong X, Retana-Márquez S, Eftekhari A, et al. Pesticide-induced alterations in locomotor activity, anxiety, and depression-like behavior are mediated through oxidative stress-related autophagy: a persistent developmental study in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(19):11205-11220. [DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c02299]

- Chakraborty S, Lennon JC, Malkaram SA, Zeng Y, Fisher DW, Dong H. Serotonergic system, cognition, and BPSD in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019;704:36-44.

- Liu Y, Zhao J, Guo W. Emotional roles of mono-aminergic neurotransmitters in major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2201. [DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02201] [PMID: 30524332]

- Svoboda J, Popelikova A, Stuchlik A. Drugs interfering with muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and their effects on place navigation. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:215. [DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00215] [PMID: 29170645]

- Kim SK, Kang SW, Jin SA, Ban JY, Hong SJ, Park MS. Protective effect of citric acid against hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in sprague-dawley rats. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(8):2823-2827. [DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.02.056]

- Banerjee C, Tripathy D, Kumar D, Chakraborty J. Monoamine oxidase and neurodegeneration: Mechanisms, inhibitors and natural compounds for therapeutic intervention. Neurochem Int. 2024;179:105831. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2024.105831]

- Yadikar N, Ahmet A, Zhu J, Bao X, Yang X, Han H, et al. Exploring the mechanism of citric acid for treating glucose metabolism disorder induced by hyperlipidemia. J Food Biochem. 2022;46(12):e14404. [DOI: 10.1111/jfbc.14404]

- Fields JK, Günther S, Sundberg EJ. Structural Basis of IL-1 family cytokine signaling. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1412. [DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01412] [PMID: 31281320]

- Wei W, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Jin H, Shou S. The role of IL-10 in kidney disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;108:108917. [DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108917]

- Sagiv SK, Kogut K, Harley K, Bradman A, Morga N, Eskenazi B. Gestational exposure to organophosphate pesticides and longitudinally assessed behaviors related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and executive function. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(11):2420-2431. [DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwab173] [PMID: 34100072]

, Aalimah Akinosho Akorede2

, Aalimah Akinosho Akorede2

, Oluwadamilola Eunice Ajibola3

, Oluwadamilola Eunice Ajibola3

, Oyeniyi Joseph Oludare3

, Oyeniyi Joseph Oludare3

, Micheal Olatunji Avoseh4

, Micheal Olatunji Avoseh4

, Olanrewaju Ridwan Adeniyi3

, Olanrewaju Ridwan Adeniyi3

, Moyosore Salihu Ajao3

, Moyosore Salihu Ajao3