Introduction

Continuous population growth and the subsequent increase in food needs and food security have been among the fundamental challenges for governments in recent decades [1-4]. Tomato paste is one of the commonly used products and is available in various packaging types and brands on the market. Additionally, according to Iran's National Standard No. 761, the addition of any preservatives, thickeners, stabilizers, flavorings, or colors to this product is prohibited [5, 6]. Due to the sensitivity of the sterilization process, any failure in this process can make tomato paste highly susceptible to mold growth [7]. Most of the time, it may be stored without a lid or come into contact with contaminated utensils from other foods. This issue can increase the likelihood of mold growth on the product. Among the toxins produced by mold growth are aflatoxins. These toxins, also known as mycotoxins, are a group of fungal toxins produced by various species of fungi, particularly those from the Aspergillus genus, specifically Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Aflatoxin (AF) contamination commonly occurs in food products, including wheat, corn, peanuts, pistachios, and soybeans [8, 9]. Consuming aflatoxin-contaminated food can cause serious illnesses in humans and animals; no living organism is safe from the harmful effects of this toxin [10]. Aflatoxins have been categorized as Group I carcinogenic agents by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which means that the agent has sufficient evidence of causing cancer in humans on repeated exposures. The AF can also lead to tissue necrosis and liver cirrhosis [11]. There are four major aflatoxins: aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2. The AFB1 is the most carcinogenic and potent of the known metabolites [12]. Then, preventing mold growth and AF production in food products is essential. Therefore, in this study, an attempt was made to investigate the exact amount and depth of contamination of tomato paste with aflatoxin during three consecutive weeks of storage at room temperature, to determine the depth of the product at which contamination occurs and how long it takes for the product to become contaminated and unusable.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

A total of 30 samples were selected randomly from a single brand with the same production date and batch number of tomato paste. They were categorized into three groups of 10 each.

Reagents and standards

The chemical substances and reagents employed in the present investigation consisted of sodium chloride (NaCl), n-hexane, chloroform (n-hexane CHCl3), methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid (CH2O2). These compounds were characterized by a high degree of purity and were procured in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) grade from Merck (Germany). The stock solution of AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2, supplied by Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), possessed a concentration of 1000.0 ng/ml. The stock solution was stored at a temperature of 4ºC in a light-protected environment. Methanol and acetonitrile were sourced from Merck Pure Chemicals (Germany). Deionized ultra-pure water was acquired from the Millipore Direct 8 apparatus. Spores of Aspergillus flavus were obtained from Sabouraud dextrose agar culture and inoculated into the culture media of 30 cans of tomato paste.

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis

The experimental apparatus and parameters established for chromatographic analysis were delineated as follows: The HPLC investigations were executed utilizing a KNAUER HPLC Platin Blue system, which was outfitted with a K-1000 pump (Berlin, Germany) and interfaced with a fluorescence detector (HPLC-FLD). The analytical column utilized in this study was a C18 column, characterized by dimensions of 4.6 x 250 mm, fabricated by Knauer in Berlin, Germany. The mobile phase employed in this investigation comprised a solvent mixture of acetonitrile, methanol, and water in the ratio of 24:25:51. Before its application, the mobile phase underwent a de-aeration process utilizing an ultrasonic bath for a period of 10 minutes. Subsequently, the mobile phase was administered at a constant flow rate of 1.5 ml/min in isocratic mode. The fluorescence detector was meticulously calibrated to function at excitation and emission wavelengths of 373 nm and 450 nm, respectively [13].

To facilitate the development of a calibration curve, six distinct dilutions of aflatoxin standards were prepared utilizing specific volumes of methanol to attain concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 ng/ml.

The verification of the analytical methodology encompassed the evaluation of its repeatability (intraday precision) and reproducibility (inter-day precision), commonly denoted as relative standard deviation (RSD). Furthermore, parameters such as linearity, accuracy (ascertained through recovery studies), selectivity, and the thresholds for detection, limit of detection (LODs), and quantification (LOQs) were meticulously analyzed. The LOD was ascertained by quantifying the concentration of the analyte, wherein the peak area was observed to be threefold greater than the background noise area in a control sample (signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 3). The LOQ was established by performing three replicates of the detection limits under the stipulation that the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) was equal to or greater than 10. The acceptable threshold for the RSD must be below 20%. Moreover, the acceptable range for recovery is expected to fall within 70% to 120% [14]. A correlation coefficient exceeding 0.99 is deemed satisfactory in the evaluation of linearity.

Inoculation of spores

Spores of Aspergillus flavus were obtained from Sabouraud dextrose agar culture and inoculated into the culture media of 30 cans of tomato paste. After incubating the fungus for 48 h at 21 °C, a suspension containing fungal spores was prepared using sterile distilled water, and the concentration of spores was measured using a Neubauer chamber. Dilution was performed so that the final concentration reached 106 /mL. Each can of tomato paste received 2 mL of this suspension [15].

Incubation and storage stages

The cans of tomato paste were stored at room temperature in an industrial kitchen (24-30 °C). The ambient temperature was monitored daily, and the cans were categorized into three groups of ten. The first group was examined after 1 week, the second group after 2 weeks, and the third group after 3 weeks.

Sampling process

After each period ended, the lids of the cans were opened, and they were first visually inspected for mold growth. Then, samples were taken weekly during three weeks from different layer depths of 1, 3, and 5 cm from the moldy surface. The level of aflatoxin in each sample was measured using HPLC.

Inclusion criteria

1. Type of Product: Only canned tomato pastes from a single brand with identical production dates and batch numbers were included in the study.

2. Appearance Status: Cans or packaging that were intact without physical damage or signs of spoilage (leaks, dents, or rust) were included.

3. Type of Packaging: Only products packaged in standard cans or jars without previous openings were considered eligible for inclusion.

4. Production Date: All samples had identical and clearly marked production dates, with no more than six months elapsed between production date and sampling time.

Exclusion criteria

1. Damage to Packaging: Cans or jars that showed signs of physical damage (e.g., leaks, rusting, and breaking) were excluded from the study.

2. Doubt about Product Authenticity: In case of any doubt about brand authenticity or product production date at any stage of the study, that sample was excluded.

3. Environmental Contamination: In case of contamination due to external pollution or uncontrollable environmental factors, the sample was removed from the study.

4. Failure to Maintain Storage Conditions: Products stored under improper environmental conditions (i.e., conditions other than the specified room temperature) were excluded.

Ethical considerations

1. Adherence to Ethical Principles in Animal and Human Testing: In all stages, the study adhered to scientific ethical principles while strictly following standards related to public health and environmental protection. No living organisms were used in aflatoxin production processes or product testing.

2. Consumer Rights Protection: All samples used served solely as laboratory samples and were not intended for public distribution or consumption.

3. Confidentiality of Information: Information regarding product brands and other confidential details was maintained throughout the study and used solely for scientific analysis.

Limitations of the implementation plan and methods to mitigate them

1. Sample Quality: One main limitation may arise from unintended changes in storage conditions at the time of sampling. To mitigate this limitation, samples were immediately placed in a controlled laboratory environment after collection.

2. Risk of Secondary Contamination: There is a risk of secondary contamination during sampling or inoculation with mold. To reduce this risk, sterilized tools and controlled laboratory environments were used.

3. Variability in Environmental Conditions: Differences in environmental conditions (variable temperatures in industrial kitchens) may affect results. To minimize this limitation, ambient temperature was monitored and recorded daily.

4. Limited Sample Size: Due to the pilot nature of this study, sample sizes may be limited. To enhance the accuracy and reliability of results, more repetitions and appropriate statistical analyses will be employed to reduce errors.

Data analysis

For AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2, a two-way ANOVA statistical analysis was conducted at two levels: week and sampling depth. After the two-way ANOVA, a One-Way ANOVA was conducted by combining the two levels of the variable’s week and depth of measurement. Subsequently, a post-hoc Tukey test was performed, revealing significant differences between consecutive weeks. Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism software. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

After implementing aflatoxin standards in the injection system, the validation of the traditional method for aflatoxin measurement in food, based on the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) method, was conducted. The results of this validation are provided in Table 1.

Table1. Validation Results of Traditional AOAC1-based Method for Aflatoxin Determination in Tomato Paste (HPLC-FLD2)

| Validation Parameter |

AFB1 |

AFB2 |

AFG1 |

AFG2 |

Notes |

| Linearity (R²) |

> 0.998 |

> 0.998 |

> 0.998 |

> 0.998 |

Matrix-matched calibration (2–50 ng/g) |

| LOD3 (ng/g) |

0.10 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

Based on S/N ≥ 3 |

| LOQ4(ng/g) |

0.30 |

0.45 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

Based on S/N ≥ 10 |

| Recovery (%) |

82.7–93.1 |

82.7–93.1 |

82.7–93.1 |

82.7–93.1 |

Spiked at 2, 5, 10 ng/g, triplicate over 3 days |

| Precision (RSD5 %) |

< 7.5 |

< 7.5 |

< 7.5 |

< 7.5 |

Intra- and inter-day precision |

| Robustness |

Passed |

Passed |

Passed |

Passed |

Stable under ±0.1 mL/min flow, ±2% mobile phase, ±2°C column temperature |

| Ruggedness (RSD%) |

< 10 |

< 10 |

< 10 |

< 10 |

Different analysts, instruments, IAC batches |

| System Suitability |

Passed |

Passed |

Passed |

Passed |

RT RSD < 1%, Area RSD < 2%, Resolution > 1.5 |

| Stability |

Stable |

Stable |

Stable |

Stable |

Extracts stable for 72h (RT & 4°C), stock standards stable 1 month @ -20°C |

| Selectivity |

No interference |

No interference |

No interference |

No interference |

Complete baseline separation |

| Measurement Uncertainty (%) |

±12 |

±12 |

Not evaluated |

Not evaluated |

Combined uncertainty at 95% CI |

1- AOAC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists.

2- HPLC-FLD: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection.

3- LOD: Limit of detection.

4- LOQ: Limit of quantification.

5- RSD: Relative standard deviation.

In this study, the results of aflatoxin production were reported from three different layers of moldy tomato paste at one-, two-, and three-weeks post-inoculation.

Regarding aflatoxin G, since no specific amount was observed, it was not included in the statistical analysis; it is only reported that no significant amounts were observed at any of the three depths or weeks measured (data not shown).

For the aflatoxins B1, B2, and B1 & B2, both levels of week and sampling depth were significant with p<0.0001.

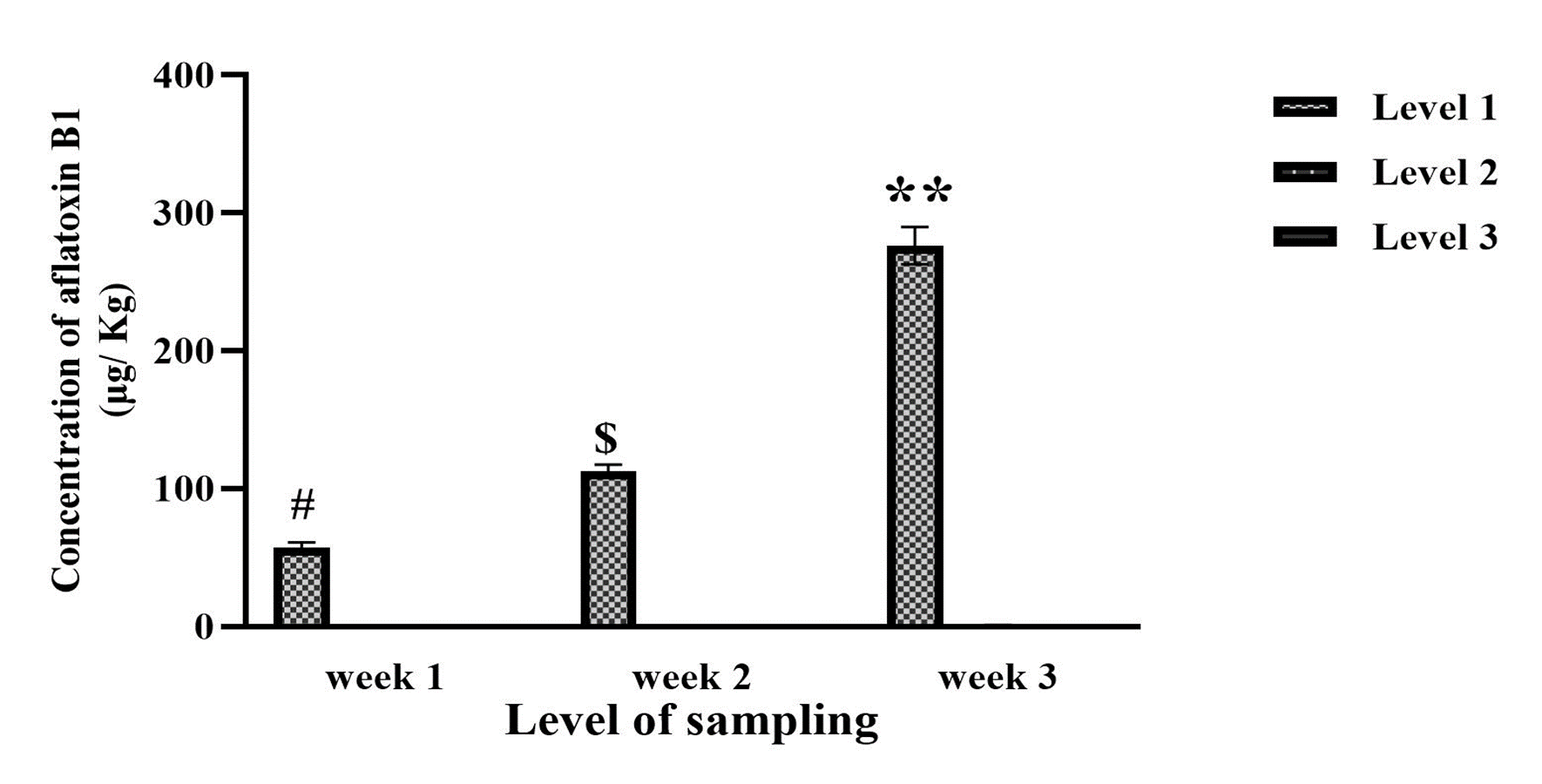

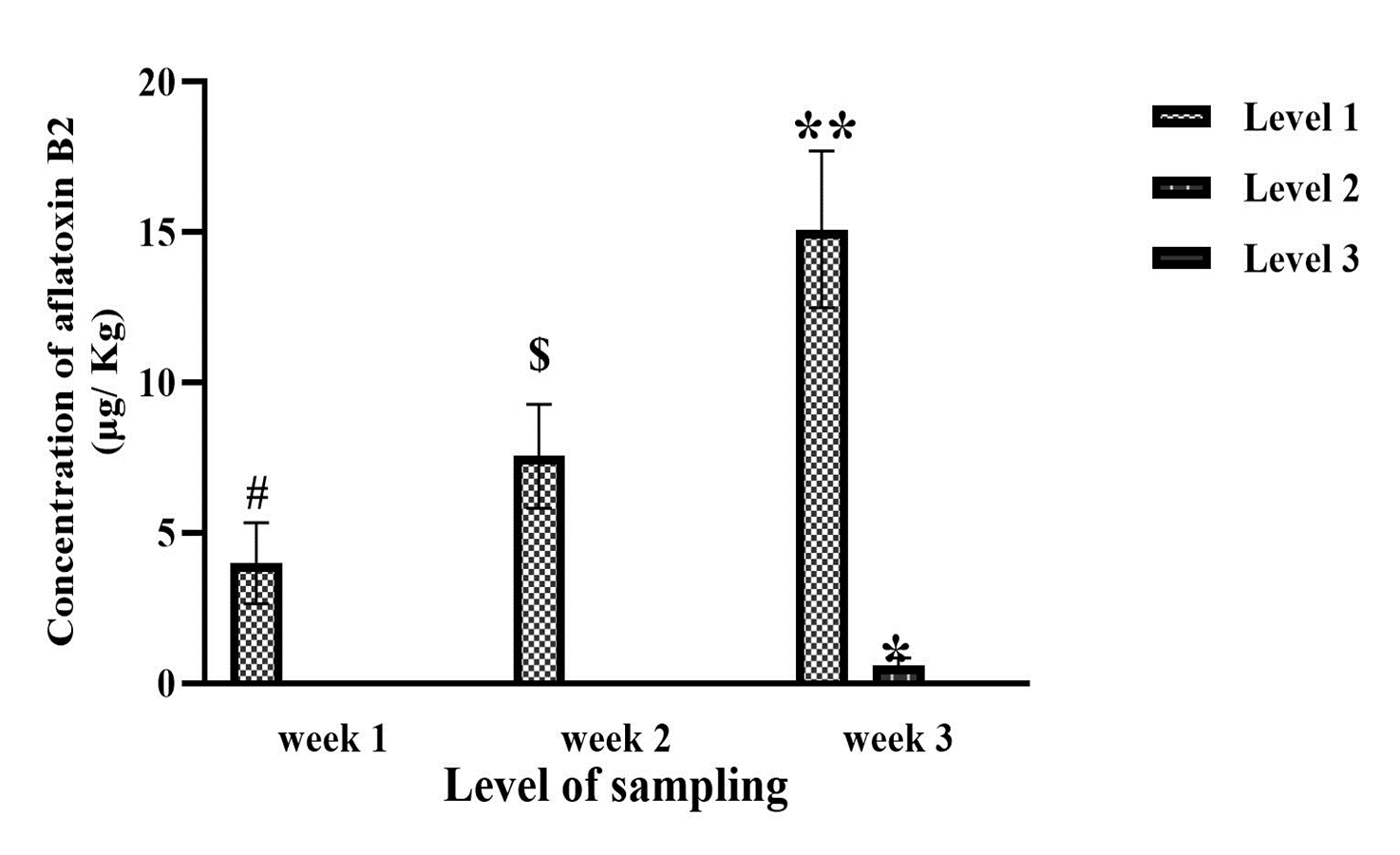

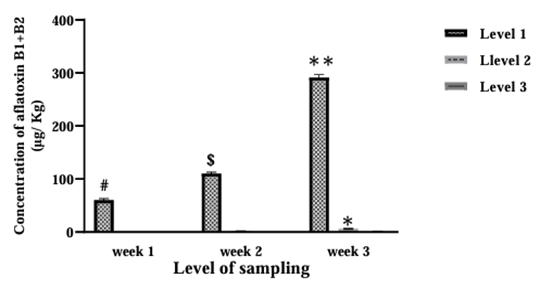

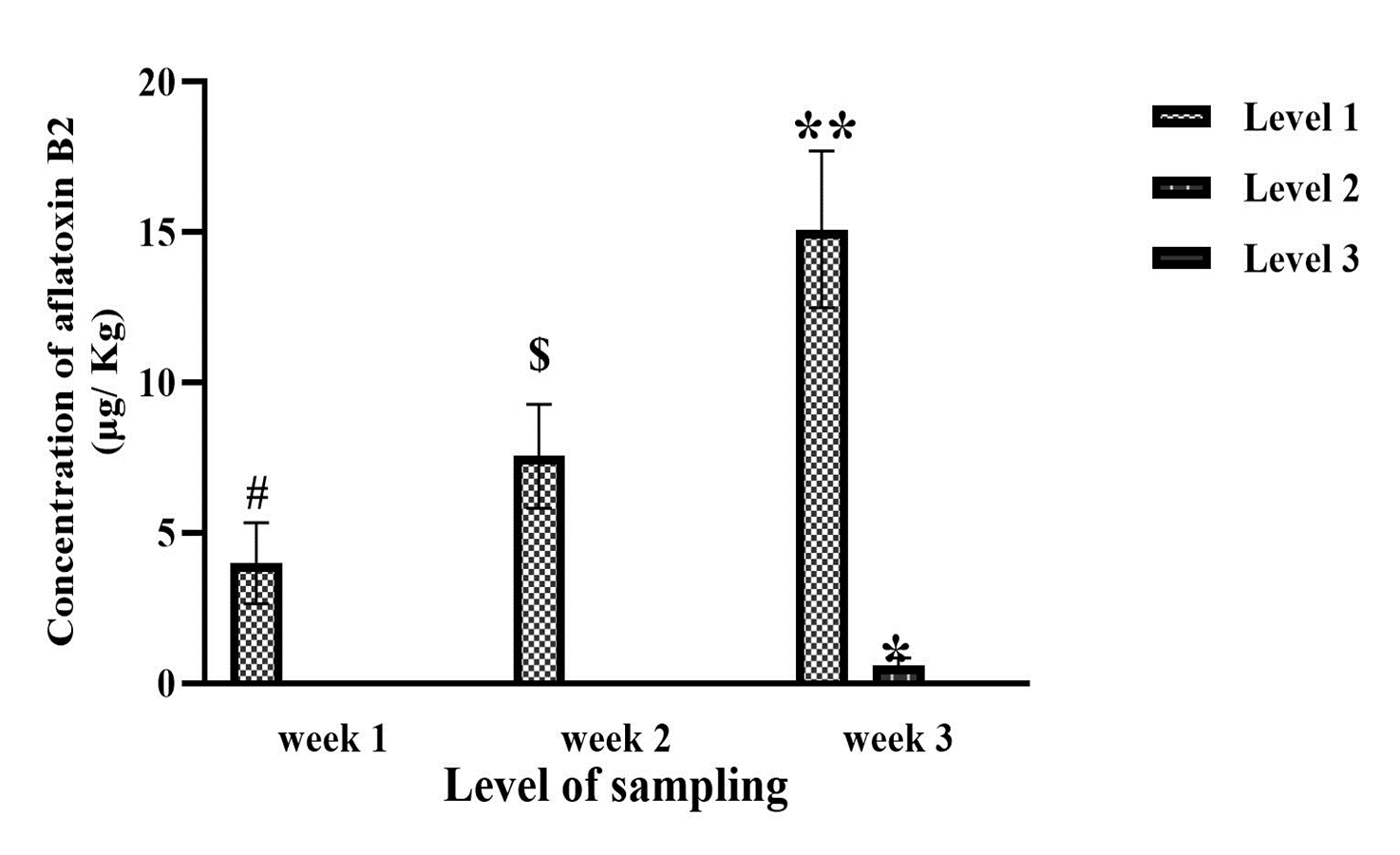

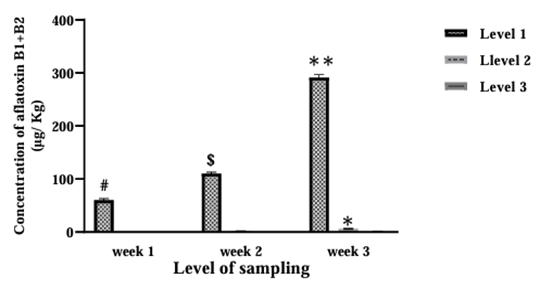

It was observed that for AFB1, AFB2 and AFB1+B2 at two levels of week and sampling depth were significance (Figure 1, Week: F (2, 261)=5321; Level: F (2, 261)=26769; p<0.0001), (Figure 2, Week: F (2, 261)=277; Level: F (2, 261)=1786; p<0.0001), (Figure 3, Week: F (2, 261)=33831; Level: F (2, 261)=150481; p<0.0001) respectively. Subsequently, a significant difference was revealed in the third week compared to the second and first weeks for AFB1, AFB2, and AFB1+B2 (Figures 1, 2, and 3; p<0.001). Additionally, the second week had a significant difference from the first week (Figures 1, 2, and 3; p<0.001). In the first week, a significant difference was observed between levels 2 and 3 for AFB1, AFB2, and AFB1+B2 (Figures 1, 2, and 3; p<0.001). Moreover, for AFB2 and AFB1+B2 in the 3rd week, a significant difference was observed compared to level 1 (Figures 2 and 3; p<0.001).

Then, it showed a significant difference for the combination of week and sampling depth for AFB1, AFB2, and AFB1+B2 (Figure 1, F (8, 261)=10630; p<0.001), (Figure 2, F (8, 261)=633; p<0.001), and (Figure 3, F (8, 261)=61548; p<0.001), respectively. The post-hoc Tukey test revealed a significant difference in the combination of the third week at all three measurement levels compared to the first week and all three measurement levels (p<0.001). However, the combination of week and measurement depth in the second week showed no significant difference compared to those in the first and third weeks.

Figure 1. Concentration of aflatoxin B1 from different layer depths of 1, 3, and 5 cm from the moldy surface kept under 24–30 °C at three-time intervals: 1-, 2-, and 3-weeks post-inoculation. Week: F (2, 261) = 5321; p<0.0001, Level: F (2, 261) = 26769; p<0.0001, **: Significant to weeks 1 & 2; p<0.001. $: Significant to weeks 1; p<0.001, #: Significant to level 2 & 3 in week 1; p<0.001, F (8, 261) = 10630; p<0.001,Week 3 & Level 1 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 2 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 3 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001.

Figure 2. Concentration of aflatoxin B2 from different layer depths of 1, 3, and 5 cm from the moldy surface kept under 24–30 °C at three-time intervals: 1-, 2-, and 3-weeks post-inoculation,Week: F (2, 261) = 277; p<0.0001, Level: F (2, 261) = 1786; p<0.0001, **: Significant to weeks 1 & 2; p<0.001,*: Significant to level 1 in week 3; p<0.001, $: Significant to weeks 1; p<0.001, #: Significant to level 2 & 3 in week 1; p<0.001, F (8, 261) = 633; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 1 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 2 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 3 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001.

Figure 3. Concentration of aflatoxin B1+B2 from different layer depths of 1, 3, and 5 cm from the moldy surface kept under 24-30 °C at three-time intervals: 1-, 2-, and 3-weeks post-inoculation. Week: F (2, 261) = 33831; p<0.0001, Level: F (2, 261) = 150481; p<0.0001, **: Significant to weeks 1 & 2; p<0.001, *: Significant to level 1 in week 3; p<0.001, $: Significant to weeks 1; p<0.001, #: Significant to level 2 & 3 in week 1; p<0.001, F (8, 261) = 61548; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 1 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001, Week 3 & Level 2 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001,Week 3 & Level 3 to Week 1 & Levels 1, 2 & 3; p<0.001.

Discussion

Tomato paste, a commonly consumed product, is susceptible to mold growth and contamination with aflatoxins if not stored properly [16]. These aflatoxins can pose health risks to humans. In this study, the concentration of aflatoxin released around moldy tomato paste, after inoculating with Aspergillus flavus spores, was examined at three depths (1, 3, and 5 cm) from the mold surface over the first three weeks under conditions simulating a commercial kitchen environment (24–30 °C). Based on conducted studies, it is recommended to use Aspergillus flavus for contaminating the samples. Additionally, some studies indicated that the optimal incubation temperature for food samples is 24–30 °C, which was also used in this study based on a comprehensive review of studies [17,18]. The results indicated that aflatoxin production in molds growing on tomato paste gradually increased over time, with these compounds penetrating deeper layers of the food. Factors such as the type of mold, storage conditions, and the physical and chemical properties of the food can significantly influence the production and penetration of aflatoxins [19-21].

According to the results obtained, during the first week, only aflatoxins from group B were present in the tomato paste, and their penetration was such that they could only spread to a depth of 1 cm. In fact, during this short time frame, the amount of aflatoxin produced by Aspergillus flavus was very low, which explains the reason for its penetration to a depth of only 1 cm. Therefore, it can be stated that if only the surface contaminated with mold is removed during this period, the remaining tomato paste is free from aflatoxins and is safe for consumption. Aspergillus flavus is known to produce aflatoxins, with B1 being the most prevalent in tomato extracts, as observed in various studies [22]. The limited penetration of aflatoxins to a depth of 1 cm suggests that the initial production is low, which is consistent with findings that peak aflatoxin production occurs after 72 h under optimal conditions [23]. The removal of the contaminated surface layer could effectively eliminate aflatoxins, as the deeper layers remain unaffected during the initial week [22]. This approach is supported by the observation that aflatoxin production can be inhibited or reduced by certain treatments, such as chitosan coatings, which have shown efficacy in reducing aflatoxin levels in tomatoes [24].

The results reported during the second week differed to some extent. In addition to the presence of group B aflatoxins in week two, group G aflatoxins were also confirmed through precise measurements using HPLC. As expected, the depth of penetration of aflatoxins increased compared to the first week, and contamination spread further. Thus, to safely consume moldy tomato paste after two weeks, 3 cm of product must be discarded to ensure that it is free from aflatoxins. The findings regarding aflatoxin contamination in moldy tomato paste highlight the increasing complexity of mycotoxin management over time. In the second week, the detection of both group B and G aflatoxins, alongside an increased penetration depth, underscores the need for stringent safety measures. The depth of aflatoxin penetration into food products increases over time, necessitating more substantial removal of contaminated layers. The recommendation to discard 3 cm of moldy tomato paste is based on empirical evidence of contamination spread, ensuring that the remaining product is safe for consumption [25]. Studies indicate that aflatoxin levels can increase significantly within a week, underscoring the importance of monitoring and promptly disposing of affected food [26].

By the third week, samples were heavily contaminated, and the aflatoxin had infiltrated throughout the product, rendering it unsafe for consumption. Aflatoxins are classified as Group I carcinogens, with Aflatoxin B1 being particularly harmful. Therefore, the entire product must be discarded as it is unusable.

Since this study was conducted at this level for the first time, the results obtained make a significant contribution to changing misconceptions about moldy products and, ultimately, their methods of consumption, thereby influencing consumer behavior and consumption patterns. Based on these results, tomato paste can be safely consumed in the first week after mold formation on its surface if more than 1 cm is removed. Additionally, after two weeks, there are no restrictions on consumption if more than 3 cm are discarded.

Environmental factors such as high moisture levels during storage significantly increase the risk of fungal growth and toxin production [27-29]. Moreover, major causes of aflatoxin contamination include improper harvesting, inadequate drying, and poor storage conditions [30]. Interdisciplinary approaches, including improved analytical methods for detection and better feed composition, can help reduce contamination risks [28].

While the initial findings suggest safety through surface removal, it is crucial to consider the potential for deeper contamination over time, especially in warm and humid conditions that favor fungal growth. Furthermore, the presence of other aflatoxin types and their precursors, which may not be as easily removed, should be monitored to ensure comprehensive food safety [31]. Additionally, when the focus is on the dangers of aflatoxin contamination, it is important to consider advancements in detection and mitigation strategies that can help manage this pervasive issue effectively. Conversely, some argue that the focus on aflatoxin levels may overshadow other potential contaminants in food products, suggesting that a more holistic approach to food safety is necessary. This perspective emphasizes the need for comprehensive testing beyond just aflatoxins to ensure overall food safety.

Conclusions

While the removal of the surface layer of tomato paste appears to mitigate aflatoxin risk in the short term, ongoing monitoring and preventive measures are essential to address potential long-term contamination and ensure food safety.

Data Access and Responsibility

The authors confirm that this article contains original

work and accept full responsibility for its content.

Ethical Considerations

Not applicable.

Authors' Contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the Research Council,

Arak University of Medical Sciences (Grant No 3982).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with any entities.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research Council, Arak University of Medical Sciences (Grant No 3982).

References

1. Ehrlich PR, Ehrlich AH, Daily GC. Food security, population and environment. Population Develop Rev. 1993;19(1):1-32.[DOI: 10.2307/2938383]

2. Ghosh A, Kumar A, Biswas G. Exponential population growth and global food security: challenges and alternatives. Bioremed Emerg Contamin Soil. 2024:1-20.[DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-443-13993-2.00001-3]

3. Alimoradian A, Tajik R, Jamalian M, Asafari M, Moradzadeh R. Assessment of non-carcinogenic risk of nitrate in agricultural products. Iran J Toxicol. 2021;15(4):257-64. [DOI: 10.32598/IJT.15.4.784.2]

4. Alimoradian A, Ansari Asl B, Asadi S, Abdollahi M, Moradzadeh R, Alimoradian K, et al. Risk assessment of colorant additives and heavy metal content of jelly products targeting pediatric populations in Arak market, Iran. Iran J Toxicol. 2025;19(2):112-20. [DOI: 10.32592/IJT.19.2.112]

5. Mohebbi M. Investigating Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Tomato Paste Using Fennel Seed Extract and Ziziphora clinopodioides Lam. and Predicting the Results Using Artificial Neural Network. J Food Sci Technol (Iran). 2023;20(141):1-16.[DOI: 10.22034/FSCT.20.141.1]

6. Madani A, Esfandiari Z, Fakhri Y. Comparative assessment of national and international stand-ards for benzoic acid and its derivatives in different types of Iranian foods: a systematic review. Iran J Pub Health. 2025;54(6):1204-15.[DOI: 10.18502/ijph.v54i6.18898]

7. Khalaf HH, Sharoba AM, El-Saadany RM, Morsy OM, Gaber OM, et al. Application of the HACCP System during the production of tomato paste. Food Biotechnol. 2021;389(402):389.[DOI: 10.21608/assjm.2021.195005]

8. Ramadan NA, Al-Ameri HA. Aflatoxins-occurrence, detoxification, determination and health risks. Intech Open 2023:1-38. [DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.92518]

9. Coppock RW, Christian RG. Aflatoxins. Vet Toxicol. 2025:1009-23.[Doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-29007-7.00043-1]

10. Awuchi CG, Ondari EN, Ogbonna CU, Upadhyay AK, Baran K, Okpala COR, et al. Mycotoxins affecting animals, foods, humans, and plants: Types, occurrence, toxicities, action mechanisms, prevention, and detoxification strategies—A revisit. Food. 2021;10(6):1279.[DOI:10.3390/foods10061279] [PMID: 34205122]

11. Chain EPoCitF, Schrenk D, Bignami M, Bodin L, Chipman JK, DEL MAZO J, et al. Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food. EFSA J. 2020;18(3):e06040.[DOI:10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6040] [PMID: 32874256]

12. Cao W, Yu P, Yang K, Cao D. Aflatoxin B1: Metabolism, toxicology, and its involvement in oxidative stress and cancer development. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2022;32(6):395-419. [DOI: 10.1080/15376516.2021.2021339] [PMID: 34930097]

13. Yazdanpanah H, Zarghi A, Shafaati AR, Foroutan SM, Aboul-Fathi F, Khoddam A, et al. Analysis of aflatoxin B1 in Iranian foods using HPLC and a monolithic column and estimation of its dietary intake. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(Suppl):83-9. [PMID: 24250676]

14. Safavizadeh V, Shayanfar A, Ansarin M, Nemati M. Assessment of the alternaria mycotoxin tenuazonic acid in fruit juice samples. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2020;9(6):1162-5. [DOI: 10.15414/jmbfs.2020.9.6.1162-1165]

15. Larone DH. Medically important fungi. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 1994;36(5):432. [DOI: 10.1590/S0036-46651994000500016]

16. Ajoke OD, Omolola DO, Olubisi BO. Mycoflora, mycotoxin, proximate and mineral composition of selected sachet tomato paste. J Biosci Biotech Discover. 2024;9(1):1-9. [DOI: 10.31248/JBBD2023.191]

17. Ju J, Tinyiro SE, Yao W, Yu H, Guo Y, Qian H, et al. The ability of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus natto to degrade zearalenone and its application in food. J Food Process Preserve. 2019;43(10):e14122.[DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.14122]

18. Durukan G, Sari F, Karaoglan HA. A beetroot-based beverage produced by adding Lacticaseibacillus paracasei: An optimization study. Quality Assurance Safe Crop Food. 2024;16(3):10-24. [DOI: 10.15586/qas.v16i3.1499]

19. Villers P. Aflatoxins and safe storage. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:158. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00158] [PMID: 24782846]

20. Kumar A, Pathak H, Bhadauria S, Sudan J. Aflatoxin contamination in food crops: causes, detection, and management: a review. Food Product Process Nutr. 2021;3(1):17. [DOI: 10.1186/s43014-021-00064-y]

21. Abrehame S, Manoj VR, Hailu M, Chen Y-Y, Lin Y-C, Chen Y-P. Aflatoxins: Source, detection, clinical features and prevention. Processes. 2023;11(1):204. [DOI: 10.3390/pr11010204]

22. Mensah JK, Owusu E, Anyebuno GA. Growth and production of aflatoxins by a flavus in aqueous fruit extracts of pepper, okra and tomato. Int J Sci Nat. 2014;5(1):1-7. [LINK]

23. Ciegler A, Peterson RE, Lagoda AA, Hall HH. Aflatoxin production and degradation by Aspergillus flavus in 20-liter fermentors. Appl Microbiol. 1966;14(5):826-33. [DOI: 10.1128/am.14.5.826-833.1966] [PMID: 5970470]

24. Segura-Palacios MA, Correa-Pacheco ZN, Corona-Rangel ML, Martinez-Ramirez OC, Salazar-Piña DA, Ramos-García MdL, et al. Use of natural products on the control of Aspergillus flavus and production of aflatoxins in vitro and on tomato fruit. Plant. 2021;10(12):2553. [DOI: 10.3390/plants10122553]

25. Aydin R. Aflatoxin contamination in animal-derived foods and health risks. Int J Nutr. 2020:5(3):26-32. [DOI: 10.14302/issn.2379-7835.ijn-19-3100]

26. Rohman A, Triwahyudi T. Simultaneous determinations of Aflatoxins B, B, G, and G using HPLC with photodiode-array (PDA) detector in some foods obtained from Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Agritech. 2008;28(3):109-12. [DOI: 10.22146/agritech.9773]

27. Shundo L, Navas SA, Ruvieri V, Alaburda J, Lamardo LC, Sabino M. Aflatoxins in peanut: quality improvement and control programs. 2010;69(4):567-70. [LINK]

28. Granados-Chinchilla F. A focus on aflatoxin in feedstuffs: new developments in analysis and detection, feed composition affecting toxin contamination, and interdisciplinary approaches to mitigate it. Aflatoxin-Control Analysis Detection Health Risks. 2017:251-80. [DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.69498]

29. Tajik R, Alimoradian A, Jamalian M, Shamsi M, Moradzadeh R, Ansari Asl B, et al. Lead and cadmium contaminations in fruits and vegetables, and arsenic in rice: a cross sectional study on risk assessment in Iran. Iran J Toxicol. 2021;15(2):73-82. [DOI: 10.32598/IJT.15.2.784.1]

30. Abdullahi N, Dandago MA. Aflatoxins in food grains: Contamination, dangers and control. Fudma J Sci. 2021;5(4):22-9.[DOI: 10.33003/fjs-2021-0504-776]

31. Schamann A, Schmidt-Heydt M, Geisen R, Kulling SE, Soukup ST. Formation of B-and M-group aflatoxins and precursors by Aspergillus flavus on maize and its implication for food safety. Mycotoxin Res. 2022;38(2):79-92.[DOI: 10.1007/s12550-022-00452-4] [PMID: 35288866].

, Seyed Mohammad Jamalian2

, Seyed Mohammad Jamalian2

, Hassan Solhi2

, Hassan Solhi2

, Aida Ghafari3

, Aida Ghafari3

, Khazra Alimoradian4

, Khazra Alimoradian4

, Amir Almasi-Hashiani5

, Amir Almasi-Hashiani5

, Nafiseh Khansari *6

, Nafiseh Khansari *6