Introduction

Acrylamide (ACR) is a chemical primarily used to produce materials known as polyacrylamide and ACR copolymers, which are used in many industrial processes, such as paper, paint, and plastic production [1]. ACR can enter the body when people consume foods that have been cooked at high temperatures or breathe in tobacco smoke. Workers in industries that use ACR may also be exposed to it through inhalation or skin contact [2]. ACR-provoked damage has been reported in various parts of the body, including the respiratory tract, reproductive system, brain, liver, and kidneys [3_5]. Following ingestion, ACR is assimilated into the gastrointestinal tract and consequently conveyed to the hepatic zone for metabolic processing via two separate routes. The primary stage entails the conversion of ACR into glycidamide, a bioactive substance that elicits genotoxic and mutagenic impacts. This transformation is facilitated by the liver-based cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2E1 enzyme, which is a CYP-dependent isozyme with a strong presence in the hepatic region [6]. The CYP enzyme system can be found in various cells, including hepatocytes and the epithelial lining of the digestive tract [7]. The organ responsible for metabolizing ACR is the liver, wherein the enzyme CYP2E1 transforms it into glycidamide. This biochemical reaction has been identified as mutagenic and linked to the onset of malignancies in diverse bodily regions [6]. The crucial CYP isoenzyme, CYP2E1, is of great importance in the metabolic pathways of both exogenous and endogenous compounds [8]. It has the potential to induce lipid peroxidation, which can lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as an outcome [9]. The harmful effects of lipid peroxides and ROS to cells are well-known, and CYP2E1's capacity to generate an array of noxious intermediate products makes it a key player in the process of tissue damage [10, 11].

ACR can undergo a different metabolic process by binding with reduced glutathione (GSH) through the action of an enzyme called glutathione-S-transferase (GST). During this procedure, GSH functions as a coenzyme, aiding in the transformation of ACR into N-acetyl-S-(2-carbamoylethyl) cysteine, a non-harmful substance that is excreted from the body through urine [12, 13]. The utilization of ACR as a substrate is a competitive process between GST and CYP2E1 [14, 15]. Elevated consumption of ACR through the mouth can harm tissues by causing oxidative stress due to depleted levels of GSH and an uneven oxidant-to-antioxidant ratio. If the GST enzyme fails to metabolize ACR due to a reduction in GSH, then the CYP 2E1 enzyme system present in the liver will change ACR into a more lethal form, glycidamide [12]. The perilous chemical substance known as glycidamide can travel to distinct tissues via hemoglobin. After arriving at the intended tissue, it can potentially combine with the genetic material of the cell and cause the growth of malignant cells that are harmful [16].

Various studies have been conducted in recent years to evaluate the effectiveness of some antioxidant compounds in improving the damage caused by toxicants. Although betaine was first identified in sugar beet juice, it has since been found in various other organisms. Once the body absorbs it, betaine plays a crucial role in preserving the well-being of critical organs, such as the liver, cardiovascular system, and kidneys [17, 18]. Betaine plays a vital role in protecting cells from stress by serving as an organic osmolyte. It also serves as a valuable source of methyl groups for the methionine cycle, leading to the formation of critical compounds. Moreover, betaine exhibits powerful antioxidant characteristics that assist in eliminating ROS. Additionally, it contributes to the body's defense system against oxidation through its involvement in sulfur amino acid metabolism [17-19]. Betaine has shown promising results as a therapeutic agent in protecting against chemical-induced kidney and liver damage [20]. This study aimed to investigate the potential benefits of betaine in protecting against ACR-induced liver and kidney damage in rats.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Betaine (C5H11NO2) and ACR (C3H5NO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich in St. Louis, MO, USA. For this study, we utilized only analytical-grade chemicals and reagents, which were acquired from either Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals and treatment

A total of 28 adult male rats (250 ± 9 g) were randomly divided into four groups. The rats in the study were subjected to a regulated light/dark cycle that lasted 12 hours each, and the temperature was maintained between 22°C-25°C. The control group was fed a balanced diet and tap water. The second group of rats received a specific dosage of ACR (50 mg/kg body weight, i.p.). Group three of animal specimens received betaine (2% in the diet) during exposure to ACR (50 mg/kg body weight; i.p.). The rats in the fourth group received betaine (2% in the diet). The present investigation has identified the most effective dosage and method of chemical administration by leveraging previous studies on ACR [21,22] and betaine [23, 24]. The amount of water and food consumed by the different groups was evaluated daily during the experimental design, and no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of food and water intake.

Following the 11-day experimental period, the animals underwent an overnight fast before being administered diethyl ether anesthesia to extract blood directly from their hearts. After extraction, the collected blood was centrifuged at a rate of 1000 g for 10 minutes to obtain plasma samples, which were then stored at -70°C. Normal saline was used to thoroughly clean the studied tissues using precise techniques. The tissue samples were divided into two portions for analysis. One of them was kept at -70°C for the assessment of oxidative parameters, while the other portion was immersed in a 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for histopathological examination.

Biochemical analysis

Plasma biochemical indices, including urea, uric acid, creatinine, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, and total protein, were assessed by commercial colorimetric kits (Pars Azmoon, Iran).

For biochemical analysis, previously frozen tissue samples were rapidly thawed and blended with a phosphate buffer solution (0.05 M, pH 7.4). After centrifugation (4000 × g for 15 minutes), the supernatant was collected for oxidative assays. The tissue activities of glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were assessed using diagnostic kits (Randox, Crumlin, UK). Additionally, the activity of catalase (CAT) was evaluated by Claiborne's method, which is based on measuring the decline in absorbance at 240 nm ascribed to the breakdown of H2O2 by CAT [25]. The levels of GSH in the tissues were assessed using spectrophotometric analysis. This involved measuring a yellow product that formed as a result of the reaction between GSH and 5,5-dithiolbis (2-nitrobenzoic acid). The absorbance of the yellow product was measured at 412 nm [26].

To quantify the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA), thiobarbituric acid was used to generate a pink compound. The solution was then analyzed for its light absorption at a wavelength of 539 nm, and the concentration of MDA was calculated based on a molar extinction coefficient of 156,000 M-1 cm-1 [27]. To determine the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) levels of the samples, the reduction of Fe+3/tripyridyltriazine by antioxidants in the samples was evaluated. This resulted in a conspicuous blue color that was measured at 593 nm for quantification [28].

The protein carbonyl groups in liver and kidney tissues were analyzed by reacting them with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine to produce dinitrophenylhydrazones. The resulting compounds were then measured spectrophotometrically at 370 nm for quantification purposes. The concentration of carbonyl groups was calculated using a molar absorptivity of 22,000 M−1 cm−1 [29].

Histopathological assessment

For histopathological examination, thin slices of liver and kidney tissue measuring 4-5 μm were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained samples were then observed under a light microscope (Olympus, CH-2) to identify changes in the histological structure [30].

Table 1 presents a quantification of several histopathological features, such as cell swelling, necrosis, hyperemia, and hemorrhage. A rating system ranging from 0 to 4 was utilized to evaluate the extent of damage caused by these abnormalities [30].

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the normality of data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized. If the data followed a normal distribution, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted, followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test to determine differences between groups. In cases where the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed using SPSS/PC software (version 21) to investigate group differences. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table1. Scoring pattern of histopathological lesions

| Grading of Lesion |

Description |

| 0 |

No abnormality |

| 1 |

Abnormalities were identified in one-quarter of microscopically examined regions. |

| 2 |

Abnormalities were detected in between one-quarter and one-half of the microscopically evaluated regions. |

| 3 |

Abnormalities were detected in between half and three-quarters of the microscopically evaluated regions |

| 4 |

Abnormalities were detected in over three-quarters of the microscopically evaluated regions |

Results

Biochemical findings

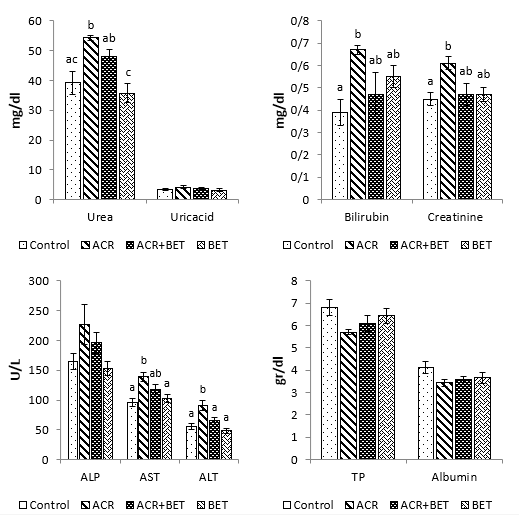

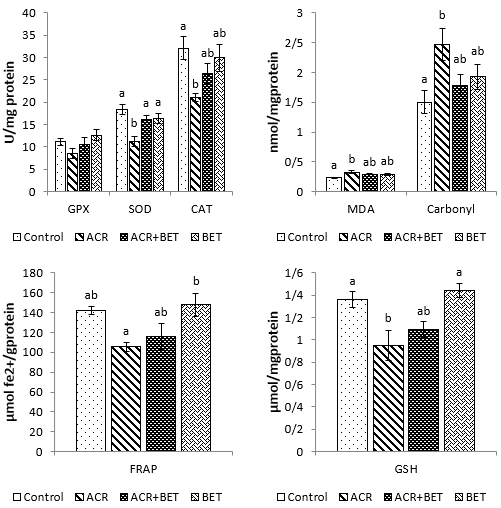

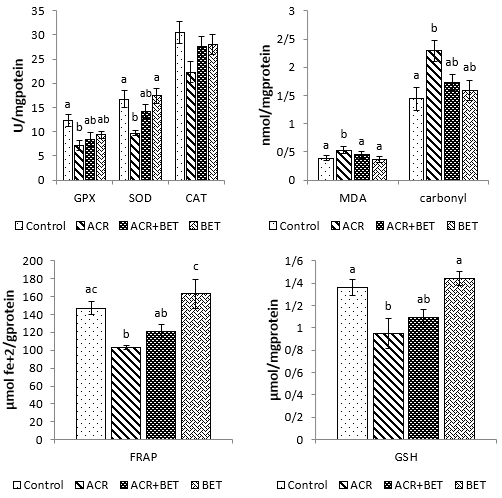

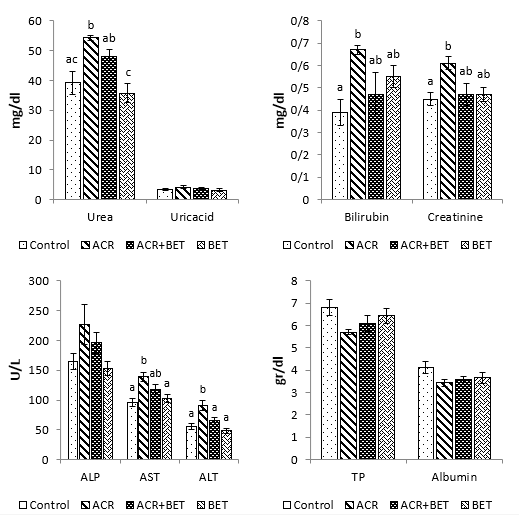

As shown in Fig. 1, the levels of ALT, AST, bilirubin, creatinine, and urea increased significantly in animals receiving ACR compared to the control group. The use of betaine in Group 3 significantly decreased the values of ALT compared to those in Group 2 and to the levels comparable to the control group. Furthermore, betaine administration in Group 3 non-significantly diminished the amounts of AST, urea, creatinine, and bilirubin relative to the second group, with quantities that showed no significant difference compared to the control group. Plasma values of ALP, total protein, uric acid, and albumin were not significantly different among the experimental groups. As shown in Fig. 2, hepatic SOD, CAT, FRAP, and GSH values showed a significant decrease in Group 2 compared to the control group. Likewise, renal values of GPx, SOD, FRAP, and GSH showed a significant decrease in Group 2 compared to the first group (Fig. 3). Betaine administration in ACR-intoxicated rats (Group 3) remarkably increased hepatic and renal GPx, SOD, CAT, FRAP, and GSH compared to the second group to values that had no significant difference compared to the controls. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, a significant upward trend in protein carbonyls and MDA levels was found in Group 2 compared to the control group in both studied tissues. On the other hand, Group 3 showed a reduction in protein carbonyl and MDA levels in the liver and kidneys after betaine administration, similar to the levels observed in Group 1.

Figure 1. Plasma Values of Measured Biochemical Indices in Experimental Groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Columns without common letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: TP, total protein.

Figure 2. Measured Oxidative Status Indices of Liver Tissue in Different Experimental Groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Columns without common letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Measured Oxidative Status Indices of Kidney Tissue in Different Experimental Groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Columns without common letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

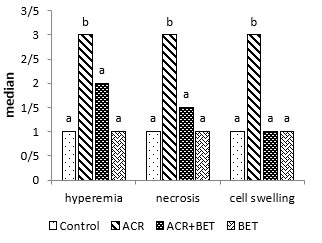

Histopathological findings

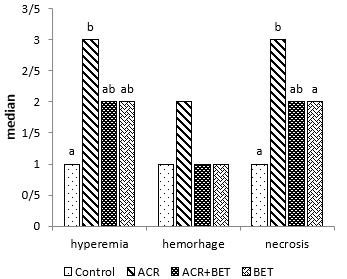

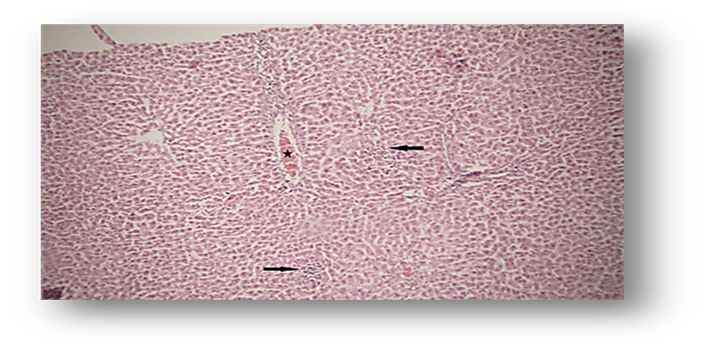

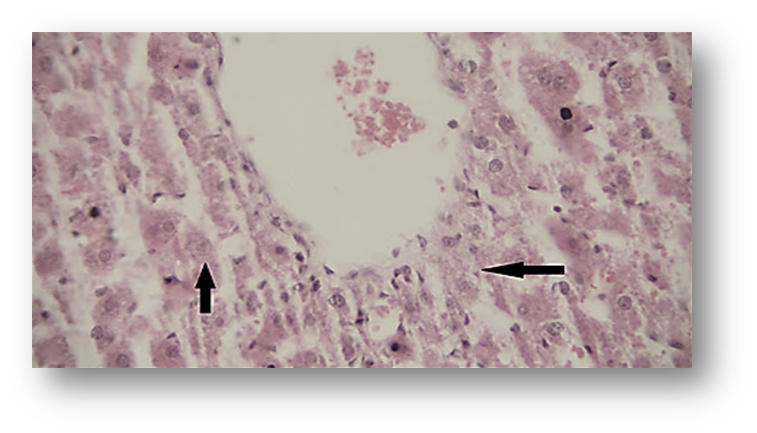

Histopathological results showed that ACR caused a significant increase in hyperemia and necrosis in the hepatic tissue of animals in Group 2 (ACR) compared to the first group (Fig. 4, Fig. 6, and Fig. 7). However, Group 3 showed a notable decrease in liver tissue hyperemia and necrosis, which did not differ significantly from the control group (Fig. 4).

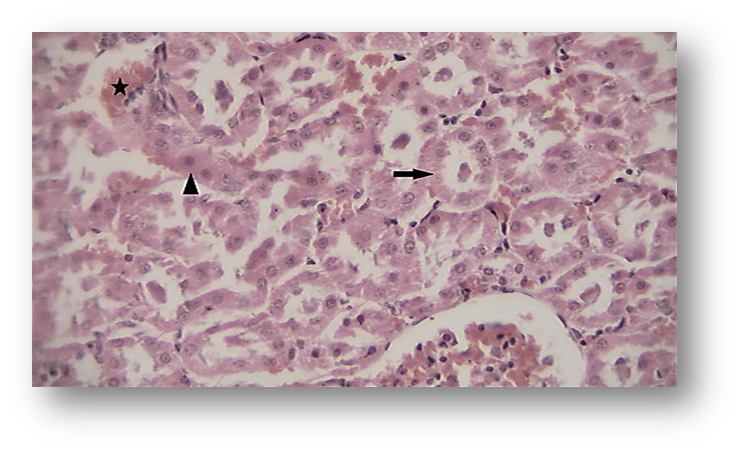

Likewise, renal histopathological evaluation (Fig. 5 and Fig. 8) showed a significant increase in necrosis, hyperemia, and cell swelling in the second group (ACR) compared to the control group. Betaine treatment in the third group was found to be significantly effective in mitigating renal pathological observations induced by ACR compared to Group 2.

Figure 4. Hyperemia, Hemorrhage, and Necrosis in the Liver Tissue. Columns without common letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).

Figure 5. Hyperemia, Necrosis, Swelling of Cells in Kidney Tissue. Columns without common letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).

Figure 6. Photomicrograph of Observed Hepatc Histopathological Features (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H&E],×100) in the Acrylamide (ACR)-Treated Group. Hyperemia (star) and necrosis (arrow).

Figure 7. Necrosis (arrow) in the Liver (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H&E],×4 00) of the Acrylamide (ACR)-Treated Group

Figure 8. Photomicrograph of Observed Renal Histopathological Features (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H&E],×400) in the Acrylamide (ACR)-Treated Group. Hyperemia (star) and necrosis (arrows).

Discussion

ACR is a toxicant found in a wide range of widely consumed foods, which unfortunately makes human exposure to this toxic substance inevitable [2, 31, 32]. This toxic chemical can damage certain body tissues; therefore, finding effective and safe compounds to alleviate the harmful effects of this chemical is crucial [3, 33]. It has been documented that a crucial underlying mechanism responsible for the tissue damage induced by ACR is overproduction of ROS and the resulting impairment of the antioxidant defense system [34]. Certain plant-derived compounds, known as phytochemicals, possess antioxidant properties that can counteract various histopathological and biochemical alterations induced by toxic substances. It has been found that betaine possesses beneficial effects upon tissue injuries caused by diverse toxicants, owing to its abilities as an antioxidant, scavenger of free radicals, and donor of methyl groups [35]. This study primarily addressed the efficacy of betaine to reduce ACR-induced nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in male rats. The liver and the kidneys have been identified as organs particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of several chemicals. The findings of the current investigation showed that ACR intoxication caused a significant decrease in hepatic SOD, CAT, FRAP, and GSH values, as well as renal GPX, SOD, FRAP, and GSH, compared to the control group. This finding is consistent with previous studies [36, 37]. Based on the current findings, it has been observed that when betaine is given to rats treated with ACR, the levels of hepatic and renal GPx, SOD, CAT, FRAP, and GSH increase. These increased levels are comparable to those in the control group and differ significantly from those in Group 2.

Previous studies have reported that betaine elevates the levels of certain antioxidant indices in various types of toxicant exposures and oxidative stress [38-40]. Moreover, hesperidin and diosmin, two antioxidant flavone glycosides, are effective in enhancing the SOD, GPX, and CAT activities in the brain, kidney, and liver of rats exposed to ACR [36]. According to reports, the use of betaine has been linked to enhanced levels of GSH that have been depleted as a result of acetaminophen consumption [41] and can normalize the changed activities of SOD, CAT, and GPX in carbon tetrachloride-intoxicated animals [24].

Antioxidants can play a significant role in curbing the proliferation of free radical reactions, which can otherwise cause extensive oxidative damage to various biomolecules. Based on the current findings, a significant ascending trend in protein carbonyls and MDA levels was observed in renal and hepatic tissues following ACR exposure. In contrast, Group 3 participants who were given betaine experienced a reduction in protein carbonyls and MDA levels in both tissues analyzed. These reductions were significant enough to bring their levels in line with those observed in Group 1 participants. Similar to these findings, thymoquinone, a natural antioxidant from Nigella sativa, diminished ACR-induced enhancement in MDA values in the rat liver, kidney, and brain [22]. Likewise, research has shown that the combined use of ellagic acid and ACR caused a decrease in MDA and protein carbonyl levels in the kidneys, compared to animals exposed solely to ACR [37]. Similarly, the beneficial influences of fresh lemon juice against hepatic oxidative changes provoked by ACR have been documented [42].

ACR-induced oxidative membrane damage can interfere with the integrity of cellular plasma membranes, leading to the leakage of certain tissue enzymes. In this study, the unusually elevated levels of circulating ALT and AST activities, as well as augmented bilirubin concentrations, denoted the severity of toxicity in the liver and were reminiscent of previously published works [43-46]. Moreover, a significant rise in circulating urea and creatinine concentration may be attributed to the loss of functional integrity of nephrocytes as described previously [43-46]. Consistent with the current findings, it has been revealed that the production of oxygen-free radicals by some toxicants induces tubular necrosis, which in turn increases tubular permeability, resulting in decreased excretion and increased retention of nitrogenous waste, i.e., urea, in the blood [47, 48]. The outcomes of the present study demonstrated a significant decrease in liver and kidney function test markers following the intake of betaine. Consistent with the biochemical indices of tissue damage, the histopathological features observed in the current study also showed toxicant-induced liver and kidney damage, which is supported by previous authors [49-51]. Moreover, betaine intake was adequate against tissue injury caused by ACR administration, which is reminiscent of the effects of betaine against ACR-induced liver and kidney injury [52], carbon tetrachloride-induced nephrotoxicity [24], hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity induced by gentamicin [35] and paracetamol [53].

Betaine has long been used as a feed additive for animals as well as a medicine for alcoholic fatty liver disease [54], hyperhomocysteinemia [55], and also against some kinds of toxicant exposures [38-40]. Combination therapy involving betaine and ACR has the potential to impede lipid peroxidation in both the liver and kidneys. This beneficial effect could be attributed to either the direct antioxidant properties of betaine or its ability to enhance the levels of certain endogenous antioxidants [56-58]. These observations indicate that the concurrent use of betaine and ACR demonstrated significant potential for mitigating the antioxidant disruptions triggered by arsenite poisoning. These data are consistent with those reported in previous studies, wherein betaine administration improved some endogenous antioxidants and decreased lipid peroxidation products in various tissues [39, 40, 56] after oxidative stress induced by a toxicant. Some observed differences between the current study and similarly reported studies [52, 58] may be attributed to variations in the experimental design, including the dose and duration of the applied chemicals, as well as differences in the analytical procedures or other unknown factors.

As a methyl donor, betaine may also increase the synthesis of key players in protein and energy metabolism in tissues, such as methionine, carnitine, phosphatidylcholine, and creatine [39, 59, 60]. Additionally, it has been documented that betaine can serve as a methyl donor for S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) restoration [61], whose important role in certain detoxification mechanisms [62] and counteracting oxidative stress [63] has been well established. Accordingly, there is evidence suggesting that SAM can enhance GSH production [57]. Besides the known antioxidant properties of GSH, its reaction with ACR via GST could be effective in the production of nontoxic metabolites, which are excreted in urine [12, 13]. Based on the current results, the administration of betaine demonstrated a certain level of effectiveness in reducing oxidative and biochemical marker indices, as well as histopathological lesions in the liver and kidneys of rats induced by ACR. Therefore, betaine has the potential to reduce the toxicity caused by ACR in the liver and kidneys. This could be attributed to its antioxidant properties and ability to act as a methyl donor, making it a promising candidate. However, it is necessary to undertake efforts towards elucidating the molecular mechanisms responsible for the ameliorative effects of betaine against ACR-induced tissue injuries. Furthermore, it is imperative to identify the correct dosage and treatment duration [46].

Conclusions

These findings indicate that betaine can mitigate ACR-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, which may be related to betaine's antioxidant and methyl-donor potential.

Data Access and Responsibility

The authors confirm that this article contains original

work and accept full responsibility for its content.

Ethical Considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran, approved the procedure (Ethics code IR.UM.REC.1400.018). This study did not raise any ethical concerns.

Authors' Contributions

Conceiving and developing the project HB and ZM; Conducting histopathological assessment and analysis: ZM; Biochemical assays and analyses: HB and JF; Writing the initial manuscript draft: HB, ZM, and JF. All authors conducted the experimental trials, provided critical feedback, and contributed to shaping the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their gratitude to the Vice President of Research and the Vice President of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine for their cooperation in conducting this study. The authors thank Mohammad Noghrei for assistance with laboratory assays.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran (grant no. 54884).

References

- Taeymans D, Wood J, Ashby P, Blank I, Studer A, Stadler RH, et al. A review of acrylamide: an industry perspective on research, analysis, formation, and control. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2004; 44 (5): 323-347. [DOI: 10.1080/10408690490478082] [PMID: 15540646]

- Lineback DR, Coughlin JR, Stadler RH. Acrylamide in foods: a review of the science and future considerations. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2012;3:15-35. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101114]

- Hamdy S, Bakeer H, Eskander E, Sayed O. Effect of acrylamide on some hormones and endocrine tissues in male rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2012;31(5):483-491. [DOI: 10.1177/0960327111417267]

- Zhao CY, Hu LL, Xing CH, Lu X, Sun SC, Wei YX, et al. Acrylamide exposure destroys the distribution and functions of organelles in mouse oocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:834964. [DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2022.834964] [PMID: 35295848]

- Hogervorst JG, Schouten LJ, Konings EJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Dietary acrylamide intake and the risk of renal cell, bladder, and prostate cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008; 87 (5): 1428-1438. [DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1428] [PMID: 18469268 ]

- A Arinç E, Arslan S, Bozcaarmutlu A, Adali O. Effects of diabetes on rabbit kidney and lung CYP2E1 and CYP2B4 expression and drug metabolism and potentiation of carcinogenic activity of N-nitrosodimethylamine in kidney and lung. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(1):107-118. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.07.026] [PMID: 17034923]

- Shimizu M, Lasker JM, Tsutsumi M, Lieber CS. Immunohistochemical localization of ethanol-inducible P450IIE1 in the rat alimentary tract. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(4):1044-1053. [DOI: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90625-b]

- Nelson DR, Kamataki T, Waxman DJ, Guengerich FP, Estabrook RW, Feyereisen R, et al. The P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers, early trivial names of enzymes, and nomenclature. DNA Cell Biol. 1993; 12 (1): 1-51. [DOI: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.1]

- Lieber CS. Cytochrome P-4502E1: its physiological and pathological role. Physiol Rev 1997;77(2):517-544. [DOI: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.517]

- Dai Y, Rashba-Step J, Cederbaum AI. Stable expression of human cytochrome P4502E1 in HepG2 cells: characterization of catalytic activities and production of reactive oxygen intermediates. Biochemistry. 1993;32(27):6928-6937. [DOI: 10.1021/bi00078a017]

- Lee, KS, Buck, M, Houglum, K, and Chojkier, M. Activation of hepatic stellate cells by TGF alpha and collagen type I is mediated by oxidative stress through c-myb expression. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2461-2468. [DOI: 10.1172/JCI118304] [PMID: 7593635]

- Sumner SC, Fennell TR, Moore TA, Chanas B, Gonzalez F, Ghanayem BI. Role of cytochrome P450 2E1 in the metabolism of acrylamide and acrylonitrile in mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12(11):1110-1116. [DOI: 10.1021/tx990040k] [PMID: 10563837]

- Ghanayem BI, Wang H, Sumner S. Using cytochrome P-450 gene knock-out mice to study chemical metabolism, toxicity, and carcinogenicity. Toxicol Pathol. 2000;28(6):839-850. [DOI:10.1177/019262330002800613] [PMID: 11127301]

- Calleman CJ, Bergmark E, Costa LG. Acrylamide is metabolized to glycidamide in the rat: evidence from hemoglobin adduct formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 1990;3(5):406-412. [DOI:10.1021/tx00017a004] [PMID: 2133091]

- Sumner SC, MacNeela JP, Fennell TR. Characterization and quantitation of urinary metabolites of [1, 2, 3-13C] acrylamide in rats and mice using carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5(1):81-89. [DOI: 10.1021/tx00025a014] [PMID: 1581543]

- Besaratinia A, Pfeifer GP. Genotoxicity of acrylamide and glycidamide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(13):1023-1029. [DOI:10.1093/jnci/djh186] [PMID: 15240786]

- Craig SA. Betaine in human nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(3): 539-549. [DOI:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539]

- Zhao G, He F, Wu C, Li P, Li N, Deng J, et al. Betaine in inflammation: mechanistic aspects and applications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1070. [DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01070] [PMID: 29881379]

- Sahebi Ala F, Hassanabadi A, Golian A. Effects of dietary supplemental methionine source and betaine replacement on the growth performance and activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in normal and heat‐stressed broiler chickens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2019;103(1):87-99. [DOI: 10.1111/jpn.13005]

- Abdel-Daim MM, Abdellatief SA. Attenuating effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester and betaine on abamectin-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(16): 15909-15917. [DOI: 10.1007/s11356-018-1786-8] [PMID: 29589235]

- Belhadj Benziane A, Dilmi Bouras A, Mezaini A, Belhadri A, Benali M. Effect of oral exposure to acrylamide on biochemical and hematologic parameters in Wistar rats. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2019;42(2):157-166. [DOI: 10.1080/01480545.2018.1450882] [PMID: 29589771]

- Abdel-Daim MM, Abo El-Ela FI, Alshahrani FK, Bin-Jumah M, Al-Zharani M, Almutairi B, et al. Protective effects of thymoquinone against acrylamide-induced liver, kidney and brain oxidative damage in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27:37709-37717. [DOI: 10.1007/s11356-020-09516-3] [PMID: 32608003]

- Junnila M, Rahko T, Sukura A, Lindberg LA. Reduction of carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxic effects by oral administration of betaine in male Han-Wistar rats: a morphometric histological study. Vet Pathol. 2000;37(3):231-238. [DOI: 10.1354/vp.37-3-231] [PMID: 10810987]

- Ozturk F, Ucar M, Ozturk IC, Vardi N, Batcioglu K. Carbon tetrachloride-induced nephrotoxicity and protective effect of betaine in Sprague-Dawley rats. Urology. 2003;62(2):353-356. [DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00255-3]

- Claiborne RA. Handbook of methods for oxygen radical research. Boca Raton. 1985; 283-284. [DOI:10.1201/9781351072922]

- Ellman, GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82 (1):70-77. [DOI: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6]

- Todorova I, Simeonova G, Kyuchukova D, Dinev D, Gadjeva V. Reference values of oxidative stress parameters (MDA, SOD, CAT) in dogs and cats. Comp Clin Pathol. 2005;13:190-194. [DOI:10.1007/s00580-005-0547-5]

- Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70-76. [DOI:10.1006/abio.1996.0292]

- Baltacıoğlu E, Akalın FA, Alver A, Değer O, Karabulut E. Protein carbonyl levels in serum and gingival crevicular fluid in patients with chronic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53(8):716-722. [DOI: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.02.002] [PMID: 18346710]

- Barangi S, Mehri S, Moosavi Z, Hayesd AW, Reiter RJ, Cardinali DP, et al. Melatonin inhibits Benzo (a) pyrene-Induced apoptosis through activation of the Mir-34a/Sirt1/autophagy pathway in mouse liver. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;196:110556. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110556] [PMID: 32247962]

- Barrios-Rodríguez YF, Pedreschi F, Rosowski J, Gómez JP, Figari N, Castillo O, et al. Is the dietary acrylamide exposure in Chile a public health problem? Food Addit Contam Part A. 2021;38(7):1126-1135. [DOI: 10.1080/19440049.2021.1914867]

- Bušová M, Bencko V, Veszelits Laktičová K, Holcátová I, Vargová M. Risk of exposure to acrylamide. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2020;28:S43-S46. [DOI: 10.21101/cejph.a6177]

- Camacho L, Latendresse JR, Muskhelishvili L, Patton R, Bowyer JF, Thomas M, et al. Effects of acrylamide exposure on serum hormones, gene expression, cell proliferation, and histopathology in male reproductive tissues of Fischer 344 rats. Toxicol Lett. 2012;211(2):135-143. [DOI: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.03.007] [PMID: 22459607]

- Zhu YJ, Zeng T, Zhu YB, Yu SF, Wang QS, Zhang LP, et al. Effects of acrylamide on the nervous tissue antioxidant system and sciatic nerve electrophysiology in the rat. Neurochem Res 2008;33(11):2310-2317. [DOI: 10.1007/s11064-008-9730-9]

- Khalili N, Ahmadi A, Ghodrati Azadi H, Moosavi Z, AbedSaeedi MS, Baghshani H. Protective effect of betaine against gentamicin-induced renal toxicity in mice: a biochemical and histopathological study. Comp Clin Pathol 2021;30:905-912. [DOI:10.1007/s00580-021-03285-2]

- Elhelaly AE, AlBasher G, Alfarraj S, Almeer R, Bahbah EI, Fouda MMA, et al. Protective effects of hesperidin and diosmin against acrylamide-induced liver, kidney, and brain oxidative damage in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(34):35151-35162. [DOI: 10.1007/s11356-019-06660-3]

- Mehrzadi S, Mombeini M A, Fatemi I, Kalantari H, Kalantar M, Goudarzi M. The effect of ellagic acid on renal injury associated with acrylamide in experimental rats. Physiol Pharmacol. 2022;26(3):313-321. [DOI:10.52547/phypha.26.4.4]

- Baltaci BB, Uygur R, Caglar V, Aktas C, Aydin M, Ozen OA. Protective effects of quercetin against arsenic‐induced testicular damage in rats. Andrologia. 2016;8(10):1202-1213. [DOI: 10.1111/and.12561] [PMID: 26992476]

- Alirezaei M, Jelodar G, Ghayemi Z, Mehr MK. Antioxidant and methyl donor effects of betaine versus ethanol-induced oxidative stress in the rat liver. Comp Clin Pathol. 2014; 23(1):161-168. [DOI:10.1007/s00580-012-1589-0]

- Hagar H, Medany AE, Salam R, Medany GE, Nayal OA. Betaine supplementation mitigates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by abrogation of oxidative/nitrosative stress and suppression of inflammation and apoptosis in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2015;67(2):133-141. [DOI: 10.1016/j.etp.2014.11.001] [PMID: 25488130]

- Khodayar MJ, Kalantari H, Khorsandi L, Rashno M, Zeidooni L. Betaine protects mice against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity possibly via mitochondrial complex II and glutathione availability. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;103:1436-1445. [DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.154]

- Haidari F, Mohammadshahi M, Zarei M, Fathi M. Effect of fresh lemon juice on oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity acrylamide-induced toxicity in rats. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2017;11(4):9-16. [Link]

- Gedik S, Erdemli ME, Gul M, Yigitcan B, Gozukara Bag H, Aksungur Z, et al. Hepatoprotective effects of crocin on biochemical and histopathological alterations following acrylamide-induced liver injury in Wistar rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:764-770. [DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.139]

- Rivadeneyra-Domínguez E, Becerra-Contreras Y, Vázquez-Luna A, Díaz-Sobac R, Rodríguez-Landa JF. Alterations of blood chemistry, hepatic and renal function, and blood cytometry in acrylamide-treated rats. Toxicol Rep. 2018;5:1124-1128. [DOI: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.11.006]

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar M, Cheraghi Farmad H, Hosseinzadeh H, Mehri S. Protective effects of selenium on acrylamide-induced neurotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2021;24(8):1041. [DOI: 10.22038/ijbms.2021.55009.12331] [PMID: 34804421]

- Abdel-Daim MM, Abd Eldaim MA, Hassan AG. Trigonella foenum-graecum ameliorates acrylamide-induced toxicity in rats: roles of oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines, and DNA damage. Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;93(3):192-198. [DOI: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0122] [PMID: 25607344]

- Suman S, Ali M, Kumar R, Kumar A. Phytoremedial effect of Pleurotus cornucopiae (Oyster mushroom) against sodium arsenite induced toxicity in Charles Foster rats. Pharmacol Pharm. 2014;5(12): 1106-1112. [DOI:10.4236/pp.2014.512120]

- Anetor J. Serum uric acid and standardized urinary protein: reliable bioindicators of lead nephropathy in Nigerian lead workers. Afr J Biomed Res. 2002;5(1-2). [Link]

- Ahrari Roodi P, Moosavi Z, Afkhami Goli A, Azizzadeh M, Hosseinzadeh H. Histopathological study of protective effects of honey on subacute toxicity of acrylamide-induced tissue lesions in rats’ brain and liver. Iran J Toxicol. 2018;12(3):1-8. [DOI:10.32598/IJT.12.3.511.1]

- Altinoz E, Turkoz Y, Vardi N. The protective effect of N-acetylcysteine against acrylamide toxicity in liver and small and large intestine tissues. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2015;116(4):252-258. [DOI: 10.4149/bll_2015_049]

- Sengul E, Gelen V, Yildirim S, Tekin S, Dag Y. The effects of selenium in acrylamide-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: roles of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and DNA damage. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:173-184. [DOI: 10.1007/s12011-020-02111-0]

- Ramadhan SJ, khadim K. Effect of betaine on hepatic and renal functions in acrylamide treated rats. Iraqi J Vet Med. 2019;43(1):138-147. [DOI:10.30539/iraqijvm.v43i1.484]

- Özkoç M, Karimkhani H, Kanbak G, Burukoğlu Dönmez D. Hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity following long-term prenatal exposure of paracetamol in the neonatal rat: is betaine protective? Turkish J Biochem. 2020;45(1):99-107. [DOI:10.1515/tjb-2018-0307]

- Day CR Kempson SA. Betaine chemistry, roles, and potential use in liver disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1860(6):1098-1106. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.001]

- Watkins AJ, Roussel EG, Parkes RJ, Sass H. Glycine betaine as a direct substrate for methanogens (Methanococcoides spp.). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(1):289-293. [DOI: 10.1128/AEM.03076-13] [PMID: 24162571]

- Kheradmand A, Dezfoulian O, Tarrahi MJ. Ghrelin attenuates heat-induced degenerative effects in the rat testis. Regul Pept. 2011;167(1):97-104. [DOI: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.12.002]

- Zhang M, Zhang H, Li H, Lai F, Li X, Tang Y, et al. Antioxidant mechanism of betaine without free radical scavenging ability. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(42):7921-7930. [DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03592] [PMID: 27677203]

- Ramadhan SJ, Khadim K. Effect of Betaine and or Acrylamide on Serum Lipids Profile and Antioxidant Status of Female Rats. Indian J Natural Sci. 2018;9(51): 15210-15221. [Link]

- Alirezaei M, Niknam P, Jelodar G. Betaine elevates ovarian antioxidant enzyme activities and demonstrates methyl donor effect in non-pregnant rats. Int J Peptide Res Ther. 2012; 18 (3): 281-290. [DOI:10.1007/s10989-012-9300-5]

- Alirezaei M, Saeb M, Javidnia K, Nazifi S, Saeb S. Hyperhomocysteinemia reduction in ethanol-fed rabbits by oral betaine. Comp Clin Pathol. 2012; 21(4):421-427. [DOI:10.1007/s00580-010-1110-6]

- Bostrom B, Sweta B, James SJ. Betaine for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia intolerant of maintenance chemotherapy due deficiency of s-adenosyl methionine. Blood 2015;126(23):1296. [DOI:10.1182/blood.V126.23.1296.1296]

- Reddy, PS, Rani, GP, Sainath, S, Meena, R, and Supriya, C. Protective effects of N-acetylcysteine against arsenic-induced oxidative stress and reprotoxicity in male mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2011;25(4):247-253. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2011.08.145] [PMID: 21924885]

- Andres A, Cederbaum A. Antioxidant properties of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in Fe2+-initiated oxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(10):1303-1316. [DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.015] [PMID: 15110395]